The John Henry Tradition- Chappell 1932

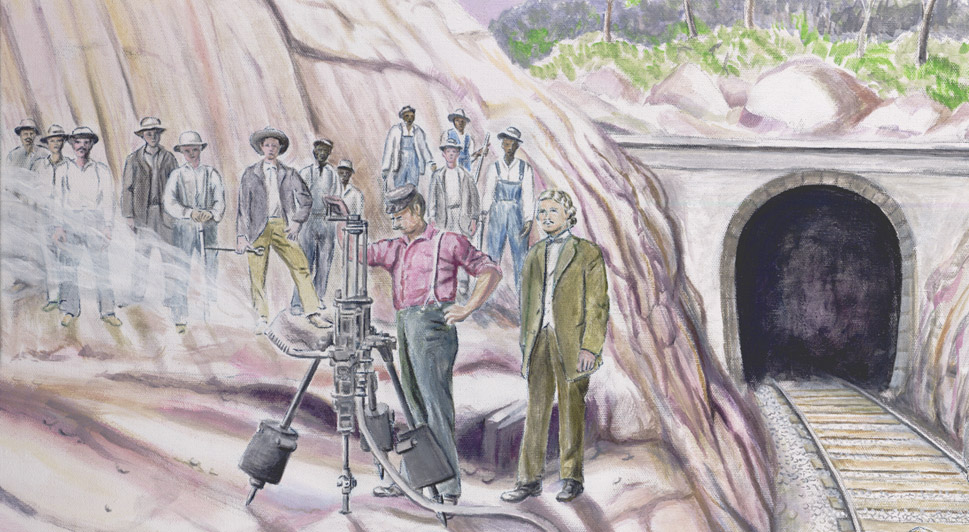

Close-Up of Steam Drill- R. Matteson C 2010

[Pictured above is Captain Dabney to the the right of the steam-drill operator.

This is Chappell's 1st chapter which begins on page 21 and follows the 20 page Introduction. It consists of testimonies about John Henry, the John Henry Song and John Hardy. Footnotes appear at the end of each page.

Chappell briefly gives an account of the Alabama origin on p. 39-40. Guy Johnson also mentioned it in 1929 but couldn't locate the "Cursey mountain tunnel" pictured above.

I'm not sure when this chapter will be completed (edited). Raw text, unedited, will be found after the first eight pages- beware!!!

R. Matteson 2014]

THE JOHN HENRY TRADITION

The John Henry tradition is widely diffused and belongs to the folk, to the lower tenth, to bums or gods as the reader may-like. He may prefer variety, or intensity. The tradition is something of an index to both, smacks of the luxuriously elemental, a prodigious reality, an articulation of what millions of toilers struggle to express, on and off, in and out, by day and by night. It is not a tale, a ballad, a song: it is all of these and more, a"living thing, and as such cannot be fully presented. "John Henry", now available in nearly a hundred variants,[1] is the best expression of the tradition.

Mr.Brown,[2] who contributes a text of the ballad, writes from Shanghai, China, that he has heard it in many places:

I've heard the song in a thousand different places, nigger extra gangs, hoboes of all kinds, coal miners and furnace men, river and wharf rats, beach combers and sailors, harvest hands and timber men. Some of them drunk and some sober. It is scattered over all the states and some places on the outside. I have heard any number of verses cribbed bodily from some other song or improvised to suit the occasion . . .

The opinion among hoboes, section men and others who sing the song is that John Henry was a negro, 'a coal black man' a partly forgotten verse says, 'a big fellow' an old hobo once said. He claimed to have known him but was crying drunk on 'Dago Red', so I'm discounting everything he said. I have met very few who claim to have known him. There was a giant yellow negro with only one arm who helped to put the Tennessee Central through the mountains between Nashville and Rockwood, Tennessee. His name was John Henry and his thumb was said to be as large as an ordinary man's wrist. He could pick up a length of the steel they were laying, straighten up turn himself completely around, still holding the rail and lower it back into place [3]. I'm not caliming this fellow is the original John Henry. He wasn't anything above the ordinary with a hammer.

This report shows more than a wide diffusion of the Henry tradition; it shows something of its character, and raises the question, Who was John Henry? with a possible answer in a "coat black man," a "big fellow", or a "giant yellow negro."

The account, however, of the a " giant yellow negro" alone offers something definite for a test on this score, but he was a lifter, not

--------------

1) See Appendix and Bibliography.

2) N. A. Brown, of the U.S.S. Pittsburgh.

3) Not an impossible task for a superman, provided the rail was a "60 or 70" not a "100 or 105", but this man would have difficulty in balancing.

_________________________________

22

a steel-driver. The large number of strong men, in one way or another connected with the Henry tradition, hardly justifies even considering this fellow as the original John Henry. He is more like the "strong man John Henry, colored", of Tallega, Kentucky, as characterized by common report. "This John Henry it was said carried three large hewn railroad ties at a time in loading freight cars. He also carried a barrel of coal oil, boxes of dry salt bacon and barrels of salt." 4) The record fails to say how many arms this strong man had.

Newton Redwine reports another John Henry of that region, a smaller man in some respects:

John Henry the steel driving champion was a native of Alabama and from near Bessemer ot Blackton. This is no doubt the man in question as he died when I was just a boy and I have heard my uncle tell of his exploits a number of times. The steel driver was between the ages of 45 and 50 years and weighed about 155 pounds. He was not a real black man, but more of a chocolate color. He was straight and well muscled.

For several years John Henry worked around the iron mining region of Alabama. Later he became a steel driver and worked on the Western & Atlantic, now the N. C. & St. L., also on the Memphis & Charleston, now the Southern from Memphis to Sallsbury, N. C. His fame as a steel driver grew each year and he was in great demand on every construction job and drove steel on practically every road under construction during his day. The Queen & Crescent was his last job.

He was well known to all the old contractors and when he had finished a job he would walk thru the mountains to another, if he had the time. He finally landed at the Kings Mountain tunnel on the route between Danville, Ky., and Oakdale, Tenn., where he worked until his death. He drove steel for four years for the Cincinnati Southern . . . John Henry drove steel with a ten pound sheep-nose hammer with a regular size switch handle four feet long. This handle was made slim from where the hammer fitted on to a few inches back where it reduced to one half inch in thickness, the width being five eights in this slim part. It was kept greased with tallow to keep it limber and flexible, so as not to jar the hands and arms. He would stand from five and one half feet to six feet from his stake and strike with full length of his hammer. The handle was so limber that when it was held out straight the hammer would hang nearly half way down. He drove steel from his left shoulder and would make a stroke of more than nineteen and one half feet spending his power with all his might making the hammer travel with the speed of lightning. He would throw his hammer over his shoulder and nearly the full length of the handle would be down his back with the hammer against his legs just below his knees. He would drive ten long hours with a never turning stroke.

. . .John Henry could stand on two powder cans and drive a drill up equally as fast as he could drive it straight down - - with the

---------------

4) The Beattyville Enterprise (a weekly), Beattyville, Ky., Jan. 4, 1929.

________________________________________

23

same long sweep and rapidity of the hammer. He could stand on a powder can with feet together, toes even and drive all day never missing a stroke. He was the steel driving champion of the country and his record has never been equaled.

There was a white man brought from some point near south Pittsburgh, Tennessee, to work in the Kings Mountain tunnel who was a good steel driver. I think his name was Duffin. They drove steel in the tunnel-heading together. They were so far under the mountain that the air was bad and stale. John Henry thought the Tennessee man would drive his hole down first and became fatigued and fell. His last words were "give me a cool drink of water before I die." This was before the completion of the tunnel. He was buried not far from the South end of the tunnel. My Uncle Solomon Archilus Knox worked with him for two and one half years. This is what I have personally heard from my uncle and other men who worked there. The best I remember it was about 1880 when John Henry died [5].

At this point the account turns to the history of steam drills, the statement, "At that time there were no steam drills ... not

an air or steam drill dependable and serviceable for nearly thirty years after John Henry's death" about 1880. Mr. Redwine should have examined Drinker's work on steam drills and tunnelling,[6]) published 1878, for an account of the steam drill as a mechanical triumph long before that date, with its subsequent use in building tunnels in Kentucky . The line 'give me a cool drink of water before I die," is found in several versions of "John Henry", which is the chronicle of the drilling-contest between John Henry and the steam drill, and which is connected with a different tunnel as this study will show.

Although the greater part of this report, showing probably an adaptation or localization from the Henry tradition, with the heroic workman either real or imaginary as in the case of others already mentioned, seems nearer fiction than fact, [7] Mr.Redwine has the support of a wide belief in a John Henry of that region. Mr. Washington [8] from Florida, says: "John Henry was a colored man and I was told by my grandfather that he was born in an old log house out a little ways from Mobile, Alabama, and that is the state where he did most of his steel- driving,- also Tennessee." Mr. Miller [9], of Virginia, adds: "My grandfather knew John Henry personally.

---------------

5. Ibid., Feb. 1, 1929.

6. Henry s. Drinker. Tunnelling, Explosive Compounds,

7. While Mr. Redwine's account of the steel-driver seems a little to much of the good thing, it is what might be called legitimate fiction if not something better, and much nearer correct as a picture than the Paul Krosen drawing of his hammer and manner of using it, "made from descriptions of the weird contest given to Johnson by an eyewitness." No steel- driver ever handled his hammer in the style of this drawing. Welch daily News, welch, W. Va., Feb. 22, 1930. For other marvel of art, see the Kewpie" artist's Jog Henry i nthe Cosmopolitan Jan. 1931.

8. J. Washington, Fort Myers, Fla.

9. Earl Miller, Hamlin, W. Va.

_____________________________________

24

He was a negro from Tennessee. The last time he heard of him he was a steel driver somewhere in Kentucky."

Another contributor, Mr. Wallace, [10] testifies to the sort of experience that qualifies him to speak with authority on the Henry vogue:

I am a steam shovel operator or 'runner,' and have heard steel drivers sing John Henry all my life, and there are probably lots of verses I never heard as it used to be that every new steel driving 'nigger' had a new verse to John Henry.

I never personally knew John Henry, but I have talked to lots of old timers who did. I have been told by some old Rail Road construction men that John Henry and John Hardy were the same man and by some others that they were not, but I believe that John Hardy was his real name. He actually worked on the C & O Ry. for Langhorn & Lanhorn and was able to drive 9 feet of steel faster than the steam drill could in Big Bend Tunnel. Then later he was hanged in Welch, W.Va. for murdering a man. After shifting out the 'chaff' think I can assure you the above is correct.

I have heard the two songs sung mostly in the same section of the country that is, West Virginia, Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina, seldom elsewhere except by men from one of the above states. I have worked all over the South, South West, and West, and have heard the John Henry song almost ever since I could remember, and it was an old song the first I ever remember of it . . .

This shift of the drilling-contest to Big Bend Tunnel satisfies the ballad account of the event, but the belief in Henry and Hardy as the same man starts something else. The report, however is purely a popular one, and it seems that the Langhorn construction company had their first contract on the road near Big Bend Tunnel in 1894, [11] about a quarter of a century too late for the origin of the tradition in the construction of the tunnel. Earl Smith. [12] who contributes a version of "John Hardy," indicates that Mr. Wallace is not alone in identifying Henry as Hardy: "1 think you find John Hardy and Henry the same man, under different names."

Objections to this identification of John Henry are too numerous to be included in this work. A good example of them is that of Miss Hayes, [13]) of Kentucky: "I am telling you all I know about John Henry. He was a negro from the state of Virginia. He was not related to John Hardy. He could lift a four ton car lift so much that his feet would go in the ground up to his ankles. He was killed in the C. & O. tunnel." Miss Hayes has probably confused the steel-driver of Virginia with one of the lifters of Kentucky or Tennessee.

-----------------

10. G. J. Wallace, Charleston, X7. Va.

11. G. L. Scott, Talcott, W. Va., states that he

furnished the Langhorns timber a construction job on the road near the east end of Big bend in 1894.

12. Of Cates, W. Va,

13. Isasbell Hayes Langley, Ky.

_____________________________________

25

An example equally typical is that of c.H. Board [14] of Virginia: "John Henry was a black man. He was not related to John Hardy. Him and Milton Brooks was little related. He was from the state of South Carolina. He died driving steel."

The confusion wiht John Hardy and John Henry is one of the problems in the Henry tradition. How well he can measure up to the popular character of John Henry can be shown.

Lee Holley of Tazewell Virginia, who claimed to be 67 years old when he made his report in 1925 offers a strong objection to such an identification , an objection with a kick:

I've lived tround here all my life. I've been acquainted with the camps in this section forty or fifty years. I remember seeing John Hardy pretty often and know all about him.

He was black and tall, and would weigh about 200 pounds, and was 27 or 8 when he was hung at Welch over in McDowell County. He was with a gang of gamblers 'round the camps. Harry christian, Lewis Rhodes, Cooper Boots, and Ben Red, and Jim Mason, and others besides were all about as bad as he was. They were all roafers and gamblers, and robbed the camps at night often after pay-day. Harry Christian was hung for killing Bill Crowe, and most of the gang got killed sooner or later."

My cousin Bob Holley drove steel with John Henry in Big Bend Tunnel. John Henry was the famous steel-driver there in building that tunnel. I heard Bob talk about him several times, but Bob's dead now. He's been dead ten years. I know John Hardy didn't drive steel in Big Bend Tunnel; he couldn't because he wasn't old enough when it was built and he didn't work anyway. He got his living gambling and robbing 'round the camps.

That this account of- Hardy is in the main correct is shown by newspaper records from that section on the occasion of his execution, January 19, 1894, for the "cold brooded" murder of Thomas Drews, also colored at Shawnee Camp, near Eckman, McDowell County, West Virginia, early in 1893. His conviction followed on october 12 of that year. The hanging took place in sight of the jail in welch, and his body was buried near the spot.[15] Who Hardy was or where he was from, is not known.

The real and popular personality of Hardy, as it appears in his documentary, testimonial, and ballad-record, is"that of an outlaw and robber, Negro desperado around the construction camps of southern West Virginia near the close of the 19th century, and has little in common with that of Henry, the heroic workman. Their confusion in oral tradition is hardly a phenomenal matter; the surprising thing

--------------

14) Montea, Va.

15) Wheeling Daily Register,. Wheeling, W. Va., Oct. 13, 1893, Jan. 20, 1894 The later reference explains why Hardy Killed Drews; in a disagreement over a crap game, "Both were enamored of the same woman, and the latter proving the more favored lover, incurred Hardy's envy, who seized the pretext of falling out in the game to work vengance on Drews."

______________________________

26

is that for a while ballad scholars found occasion to add this confusion.[16]

Mr Redwine described his John Henry as "not a real black man but more of a chocolate color," and introduced a white man, a superior steel-driver from Tennessee, who, he thinks, was named Duffin, and who, with the aid of bad and stale air, forced his champion to the wall. This event, real or fictitious, may have some bearing on the popular belief in John Henry as a white man from Kentucky or Tennessee.

Two reports from North Carolina are definite on the question of Henry's color. Mr. Kelley [17]; writes: "I have heard old men talk about John Henry that knew him. He was born in Tennessee and was a white man. His steel driving buddy was Ben Turner.[18]). But where he worked I don't know." Mr. Webster [19]) adds: "The contest between John Henry and the steam drill took place in the Big Bend Tunnel on the C. & O. Railway. . . He bet a thousand dollars that he could out do the drill, and did so, but died shorily afterwards. He was a white man." Mr. Webster fails to say where Henry got the thousand dollars.

Hazel Underwood, [20] of West Virginia, reports the Henry tradition in her family:

My father has often told me about John Henry. He says he man of about 35 years old, strong built, had muscles was supposed to be like iron. He drilled holes in the big rock cliffs with his strong arms and his two hammers one in each hand day after day.

There is no mistake about his being a white man. Papa says his last drive was made in the Big Bend Tunnel on New River. Father says he has heard when he was a boy all about him and learned the song when he worked in the log camps, but had forgotten it till he heard part of it on a Record we have, it is just a part of it. Mamma and Pa says they can't believe this is all.

This account has a popular ring, and somewhat less authority than that of Mr. Gregory,[21] another West Virginian, who reports the "old original song of John Henry", and who claims that John Henry was a white man.

Mr. Roberts, [22] of the same state, along with his account of Henry as a white man' represents him as doing something besides work:

----------------

16) See "John Hardy," philolosical Quarterly, IX, 250ff

17) J. H. Kelley, Harrisburg, N. C.

18) It is all probable that Joe Turner had something to do with the belief in Henry -as a white m-an and his connections in Tennessee? See Odum and Johnson, The Negro and his Songs, p. 206ff. W. C. Handy. Blues: An Anthology, p. 40ff. (I fail to find that an "ideal is hinted at" in Odum and Johnson's text of "Joe Turner", or, Handy's idea that in this text "Joe is supposed to be a convict himself").

19) H. Webster, State Hospital, Morganton, N.C.

20) Huntersville, W. Va.

21) V. E. Gregory, White Sulphur Springs, W. Va.

22) George W. Roberts, Sweetland, W. Va.

________________________________________

27

John Henry was a white man, an American born English by birth. His weight -- 240 lbs at the age of 22. The muscle of his arm was 22 inches around. Many times have I seen his woman but never John Henry personal- but, have worked in the mines for years with the old Welshman that sharpened tools for him by the name of Billy McKenzie.

John Henry was a native of Virginia and did actually kill himself driving steel at the Big Ben tunnel on the C. & O. R. R. in the year of 1873. He was in the penitentiary for killing a man and the contractors got him out to drive steel. He was no relative of John Hardy at all.

I am near 70 years old, and I was a miner for a great many years in the Kanawha valley at Paint Creek after the C. & O. was built, and that is the place I used to see John Henry's wife a little ugly freckle-face woman. She would come around the mines where the work was going on.

McKenzie's widow [23] says she does not remember that her husband ever spoke of Henry or his wife in her presence. The "freckle face woman" however will appear several times in a later chapter. She has value here only al a possible influence in the belief in John Henry as a white man and a criminal.

The same belief is reported from Virginia and Kentucky. Harry Hicks [24] writes:

John Henry was a white man they say. He was a prisoner when he driving steel in the Big Ben tunnel at that time, and he said he could beat the steam drill down. They told him if he did why they would set him free. It is said that he beat the steam drill about two minutes and a half and fell dead. He drove with a hammer in each hand, nine pound sledge. . .

This is a popular report, and shows for Virginia more than an individual belief in Henry as a white man with a past. That from

Kentucky is somewhat different. Mr. Barnett, [25] who claims a career working on railroads and around the coal-mines", says that he has always heard that either Henry or Hardy was a white man and a "ruff'an" from Kentucky.

Mr. Thompson, [26] a merchant, with contacts of another sort, has heard of Henry and Hardy in Tennessee:

Having been born and raised in the state of Tennessee and, therefore in sufficiently close contact with the negro element there, it happens that I have heard these songs practically all of my life, until I left that section six years ago . . . I have been informed that John Henry was a true character all right, a nigger whose vocation was driving steel during the construction of a tunnel on one of the southern railways. I heard the John Henry song, long before I did John Hardy. It has always been my understanding that John Hardy was a western character, probably a train robber.

---------------

23) An elderly woman who divides her time among her children of Hinton and Montgomery, W. Va.

24) Evington, Va.

25) W. P. Barnett, of Magoffin County Ky.

26) B. E. Thompson, Sutton, W. Va.

_______________________________________

28

He undoubtedly understands the western character to be a white man.

Two other contributors, both of West Virginia, characterize Hardy as a white man. Mr. Peters [27] "can not say" about Henry, but explains that Hardy was a "white man lived in Logan county this state. He killed a man by the name of Vance [28] over on the Big Sandy River in a log camp." Dr. Cox obtained from a certain Mr. Walker a "current report"' in southern West Virginia "concerning a John Hardy who was a tough, a saloon frequenter, an outlaw, and a sort of thug. He [Mr. Walker] thinks this John Hardy was a white man, and is sure that he was hung later on for killing of a man in McDowell county or across the line in virginia. [29]

In a few of their songs, Henry and Hardy seem to have rather close white companions. A blue-eyed woman is the apparent cause the outlaw's troubles in two versions of "John Hardy" one from North carolina and one from Kentucky, [30] and the

steel-driver takes leave of his blue-eyed "baby" in a Virginia text of the John Henry song.[31] .Although questions may be raised about this motif as showing a belief in the two ballad figures as white men, it falls in line with the testimonial data, and this angle to the Henry tradition cannot be ignored.

The race of Hardy has been determined by his identification as the Negro desperado hanged in 1894 in southern West Virginia, but his confusion in oral tradition with John Henry and a notorious white outlaw of that section must have un important bearing on the belief in Henry as a white man, and possibly as a criminal also. Hardy might well be the contact man. Mr. Walker reported a white John Hardy a "sort of thug," hanged for murder in McDowell county or across the line in Virginia, and Mr. Barnett has always heard that either Henry or Hardy was a "rufr'an" from Kentucky. This identification of this man is important.

In 1925 Ben Hardin was featured in a newspaper of that locality. Mr. Morton, a small boy at the time of Hardin's execution writes:

Ben Harden - - many of our older citizens will remember this distinguished criminal who was hanged at Tazewell courthouse on June 28, 1867, for the murder of Sanderlin Burns, who also was a Kentuckian and horse drover. Harden proposed to Burns to swap saddles, in a back alley and asked Burns how he would trade. Burns replied to him and said, 'I will swap just as though you had none' . . . Harden left the scene and went to some one and got a double-barrelled shotgun ... and shot Burns Harden was indicted at the May term of the circuit court, 1867, and was

----------------------

27) J. M. Peters, Huntington, W. Va.

28) This may be a confusion with Abner Vance, a Baptist preacher who killed Lewis Horton in that region. See Folk Songs of the South, p. 207.

29) Journal, XXXII, 510.

30) Appendix, p. 137, Campbell and Sharp. English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, p. 257.

31) Appendix, p. 99.

____________________________________

29

The jury brought in a verdict of guilty of murder in the first degree. After sentencing Harden to be hanged the Judge asked him if he had anything to say, and he responded, 'If this had been done years ago it would have been better for me and many others.[32]

Two of these older citizens have made pertinent statements about the outlaw. John McCall, who "saw it all and remembers it as if it were yesterday", says his name was John Benjamin Harden. Samuel Spurgeon, who was also at the hanging, states that he "went by the name of Ben Hardin usually," and was "sometimes called John Hardin" too, and even John Hardy or Ben Hardy, but his real name was John Benjamin Harding." He remembers that Ben Hardin was a bad man, "with long black hair and a wicked look." Mr. McCall remembers that the murderer rode to "his hanging in a wagon seated on his coffin". They agree that the rope broke, and that he had to be hanged the second time. Their account of his spectacular taking-off suggests that one might expect him to gain high place in the popular repertories of that locality.

This testimony has the support of the Clinch Valley News and other newspapers of the time.[33] One correspondent became

rather dramatic in his "Execution of a Hardened Wretch."[34] If anything further was necessary to put Ben Hardin on the honor roll of his profession, it followed in his ten-thousand-word "Autobiography," with a caption notable for its omissions:

Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin Harden, executed at Tazewell Court H[ouse] on the 28 th of June, 1867, for the murder of Dennison T. Burns, the 16th day of April, 1867. Startling confessions! Boys, take Warning! Fate of the spoiled child, the disobedient boy, the roguish lad, the stealthy house-robber, the dashing highwayman, the daring horse-thief, the twofaced friend, the unprincipled intriguer, the successful swindler, the heartless seducer of female innocence, and the cold-blooded assassin of seven defenceless and unsuspecting victims. [35]

Nothing is known of Ben Hardin, except the events connected with execution. [36] He claimed to be from Kentucky, and was hanged for killing a man, not in McDowell county, but across the line in Virginia. That he is the white man in the Henry tradition seems almost certain, although others, such as the white steel-driver from Tennessee and the "freckle face woman," cannot be entirely ignored, certainly not in their respective localities. Yet, in the nature-of things, even an approximate measure of such influences cannot be made.

------------------------------------

32) Bluefield Daily Dispatch, Bluefield, W. Va. Aug.30, 1925.

33) Lynchburg Daily Virginian, Lynchburg, April 27, 1867.

34) Ibid., July 4, 1867.

35) Clinch Valley News, Tazewell, Va. Copy of extra edition in 1867, and subsequent to the execution of Ben Hardin, now in my

possession. Its files begin around 1900.

36) For the court iecords of Hardin's trial. see John Newton Harmon. Annals of Tazewell County II. Fuller account of the outlaw may found in my article: "Ben Hirdin," Philological Quarterly, X, 27ff.

________________________________

30

The age of the Henry tradition, as noted in testimony and documentary accounts, should prepare the way toward its place of origin. But, unfortunately, several of the reports are too indefinite on that score.

The following is an example:

I was reared in South Carolina, and there I often heard colored men, while driving with heavy hammers, sing this much of the song in question, which seemed to be the chorus:

'This is the hammer that killed John Henry, but can't kill me;

This is the hammer that killed John Henry, but can't kill me.'

I heard one man relate to another that John Henry was a negro convict (possibly of the state of South Carolina) who at that time was hired out to a quarry company, that John was such a powerful man a bet was made on him and a race was staged with the steam drill. The drill beat him ten inches in a day, and that night John Henry died. [37] Another of the sort comes from Mrs. Susan Bennett:[38]

Wish to say that there was a man of that day in making big ben tunnel that whipped the steam drill down. I live in about 25 miles of the tunnel and it is as true as the song Pearl Bryant or Jessie James or George Alley and you may write to the Bureau of Information and get the History of John Henry and his captain's name. We have 3 records of Johnie so I will close and listen at him drive that steel on down.

In this case, however, I was able to visit the contributor at her home a few months after receiving her report by letter, and found that she had known about John Henry from the time Big Bend Tunnel was built, between 1870 and 1872.

Elizabeth Frost Reed, of Vest Virginia University, reports the following lines heard sung, in 1909, by Lewis Lytle, a Negro on her

father's farm at Flat Creek, Tennessee:

When the women of the West hear of John Henry's death,

They will cry their fool selves to death.

In 1900 or 1901, Mr. Bonham heard of John Henry from a grade foreman by the name of Surface, as truthful a man as he has ever met, when they were double-tracking the Norfolk and Western Railroad. "According to Surface, John Henry died after he had won the famous contest wielding two 18-pound hammers, one in each hand." [39]

Several others first heard of the steel-driver about this date. Mrs. McKnight, [40] of Kentucky, writes: "My husband was very much interested in 'John Henry' . . . I don't know where he got the John Henry

----------

37) J. T. Baker, clergyman, in The Bradford News Journal, East Bradford, Va., Jan. 10, 1929.

38) Landisburg, W. Va.

39) The Bradford News Journal, East Bradford, Va., Jan. 10, 1929.

40) J. L. .McKnight, Conway, Ky., sent a text of "John Henry, '' a few days before he was killed in a railroad accident, and Mrs. McKnight, answered the second letter to her husband.

________________________________________

31

song, or how long he had known it. He knew this song when I first met him more than 30 years ago." Burl McPeak [41] another Kentuckian savs, "My father learnt it from a colored man on the C and O road about 1904." Mr. Murphy, [42] of Virginia, fails to know "anything definite about John Henry but about the year 1900 I first began to hear the song-long before talking machine Records was known in this section."- Mr."Barnett,[43] of West Virginia, says, "It has been years since I learned the song of John Henry". Mr. Boone [44] whose "life, up to 1925, was spent in the West Virginia hills over in the Oreenbrier Valley," sends from Pennsylvania a text each of the Henry and Hardy ballads, and states: "I do not remember just the exact date I first heard the songs, but it was the colored men working on the construction of the Greenbrier Division of the C. and O.

Ry. I first heard sing the songs. It seems to me it was about 1899 or 1900." Two versioris of "John Hardy" in which lines of "John Henry" seem to go back to this peqiod. [45] These reports indicate a wide circulation of the Henry tradition by 1900, and point to an earlier date of origin.

The same situation obtains for the tradition in the last quarter of the 19th century:

Joe Wilson, Norfolk, Va. In 1890 people around town here were singing the song about John Henry, a hammering man, hammering in the mountains four long years. I was working in an oyster house here for Fenerstein and Company, and I am

66 years old and still working for them people.

Tishie Fitzwater, Hosterman, W. V a. I have heard of him for 40 yearr. A old colored man told me that John Henry was a

colored man and he was a cousin to him. I have never heard any one say that John Henry was any relation to John Hardy, and I am sixty years old.

R. H. Pope, Clinton, N. C. Well I know of the song 41 years. I went to Georgia 1888, and that song was being sung by all the young men. I am now 60 years of age. In those days I knew all the words of that song but can't remember all of them now, but it was that he would die with the hammer in his hand before he would be beat driving steel . . . He was a negro and a real man so I was told.

Q. W. Evans, Editor of The New Castle Record, New Castle Va. The writer is a man in the 50's, but as a boy and young

man I can distinctly remember the song, the tune, and some of the verses, which I remember were quite a number ... The negroes of forty years ago regarded him [John Henry] as a hero of their race.

W. C. Handy, New York City. As a composer of Negro music I seized on a melody that I used to hear when I was a little boy, at

-----------------------

42. Fords Branch, Ky.

43. D. Murphy, N. P., Council, Va.

44. Barnett, Holstead, W. Va.

45. D. O. Boone, Knox, Pa.

46. Folk-Songs of the South, p. 178. The West Virginia Review, (August, 1931), p. 368.

___________________________________

32

Muscle Shoals canal in Alabama. I printed this under the title JOHN HENRY as I had heard it. 46)

Andy Anderson, Huntington, W. Va. About 45 years ago I was in Morgan county, Kentucky. There was a bunch of darkeys came from Miss. to assist in driving a tunnel at the head of creek for the o & K. R R company. There is where I first heard the song, as they would sing it to keep time with their hammers.

Jesse Sparks, Ethel, W. Va. My father is 87 and he says it has been a song ever since he can remember. He says he has

heard grandpa sing it .. . I am 37 years old myself, and, I have been knowing it ever since I have been big enough to sing.

This testimony shows the Henry tradition widely diffused as early as the eighties, the latest date possible for its origin.

introduction of the steam drill into railroad construction in this country soon after the Civil war marks the date before which it could hardly have started. It must, then, belong to the period between these two dates.

Several of the reports connect the tradition with Big Bend Tunnel on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad. George Johnston [47] adds a fuller account:

John Henry was the best driver on the C. & O. He was the only man that could drive steel with two hammers, one in each hand. People came from miles to see him use the two 20 lb. hammers he had drive with.

It seems that two different contracting companies were meeting in what used to be called Big Bend Tunnel. one had a steam drill while the other used man power to drill with. When they met everyone claimed that the steam drill was the greatest of all inventions, but John Henry made the remark he could sink more steel than the steam drill could. The contest was arranged and the money put up. John Henry was to get $100.00 to beat the steam drill.

John Henry had his foreman to buy him 2 new 20 lb. hammers for the race. They were to drill 35 minutes. When the contest was over John Henry had drilled two holes 7 feet deep, which made him a total of 14 feet. The steam drill drilled one hole 9 feet which of course gave the prize to John.

When the race was over John Henry retired to his home told his wife that he had a queer feeling in his head. She prepared his supper and immediately after eating he went to bed. The next morning when his wife awoke and told him it was time to get up she received no answer and she immediately discovered that he had passed to the other world some time in the night. His body was examined by two Drs. from Baltimore and it was found his death was caused from a bursted blood vessel in his head.

------------------

46) Excerpt from a personal letter. Mr. Handy was born Nov. 16, 1873 Blues: An Anthology, p. 18.

47) Lindside, W. Va.

_________________________________

33

The information I have given you came to me through my grandfather. He was present at Big Bend Tunnel when the contest was staged, at that time he was time 'keeper for the crew that John Henry was working with. I have often heard him say that his watch started and stopped the race. There was present all of the R. R. officials of the C. & O. The crowd that remained through the race at the mouth of the tunnel was estimated at 2500 a large crowd for pioneer days.

John Henry was born in Tenn. and at the time of his death he was 34 years old. He was a man weighing from 200 to 225 1bs. He was a full-blooded negro, his father having come from Africa. He often said his strength was brought from Africa. He was not any relation of John Hardy as far as I know.

Considerable verisimilitude hardly characterizes all these details. The presence of all the officials of the road, with a crowd of 2500, at the drilling-contest had better be accepted as fictional embroidery. But the purpose of this study is not to emphasize the tissue of falsehood in popular reports. Big Bend Tunnel was built by a single contractor, as will be shown later, but the "two different contracting companies" may well represent two crews of workmen. The steel-driver at that time may have had "2 new 20 lb. hammers" and used only one at a time. Two doctors from Baltimore may have examined Henry's body, but that they came to the tunnel for that purpose seems impossible of belief. His John Henry suggests the frontier strong man, who does impossible things.

Pete Sanders, an old Negro, who claims to be from Franklin County, Virginia, has lived for many years in Fayetteville, West

Virginia, where with tales old and new, he often enteriains youngsters about town. Long years ago he learned an Indian war whoop, and occasionally , early in the morning or late in the evening, gives it from a nearby mountaintop. He says of Henry's connection with Big Bend:

I didn't drive no steel in Big Bend Tunnel. Uncle Jeff and Eleck did though, and saw John Henry drive against the steam drill, and died in five minutes after he beat it down. They said John Henry told the shaker how to shake the steel to keep it from getting fastened in the rock so he couldn't turn it. He told him to give it two quick shakes and a twist to make the rock dust fly out of the hole.

i heard the song of John Henry driving steel against the steam drill when they were still working on the C. and O. It was all amongst us when I was a boy. When we were boys there in Franklin County worked on the extension of the railroad up in Pocahontas County, we carried the song with us there and carried it back home went we went. It was the leading railroad song, but they've tore it all to pieces and sp'iled it. I head it the other day on the machine, but it ain't noways like it used to be.

They said Big Bend Tunnel was a terrible place, and many men got killed there. And they throwed the dead men and mules and altogether there in that fill between the mountains. Uncle Jeff and me come in West Virginia together when I first come, and he showed me the big fill and said they tried to put John Henry there first, but didn't do it

___________________________________________

34

and put him somewhere else. The dumper at the fill was the man that knowed all about it. Uncle Jeff said one day a long slab

of rock that hung down from the roof fell and killed seven men. He said he seen 'em killed, and they put 'em in the fills. The people in the tunnel didn't know where they went.

Mr. Sanders, obviously, would not be the first to object to the popular account of building the Chesapeake and Ohio:

Kill a mule, buy another,

Kill a nigger, hire another.

The "extension of the railroad up in Pocahontas County," West Virginia where he and others carried "John Henry" as the leading railroad song, is the Greebrier Division of the C. and o. Ry.", where Mr. Boone first heard Negroes singing it around 1900.

Erskine Phillips, editor and publisher of the Fayette Democrat, at Fayetteville, west Virginia, is well acquainted with the southern part of the state from several years' experience as a surveyor. He says:

I had a very interesting conversation with an old negro here sometime ago. He, Ben Turner, and his brother, Sam, are natives of Old Virginia and migrated to West Virginia, along with hundreds of other 'niggers' to work on the c. and o. Railway. They both worked in the Big Bend Tunnel. John Henry was a powerful man, large all over, but possessed of the 'most powerful arms and shoulders I ever saw. Why! man', he said, 'his arms was as big as a stovepipe. Never seen such arms on a man in my life.'

'Could he drive steel the way the song says he could?' I asked, 'Law, I reckon he couid. Make that steel ring just like a bell. But look here. John Hardy (he spoke of him both as Henry and Hardy) had a steel turner almost as big and strong as he was. Just the same as two men driving. That man could turn the steel and hit almost as hard as John Henry could. John Henry wouldn't let no one else turn steel for him.' The John Henry song was not the one that was generally sung by the steel-drivers. If some one were hurt or killed in the tunnel, the foreman would yell, "All right, boys, let's hear "John Henry".' The song had the effect of sobering the workmen, taking their minds of the accident and restoring order.

Not a single detail of this re.port even slightly suggests that Ben Turner ever saw either John Henry or Big bend Tunnel. The foreman would hardly call for the ballad record of Henry's death in the tunnel as a means of "sobering the workmen" when some one else got killed there, certainly not in a tunnel without an official casualty list. Moreover, the Negroes of the community are still afraid of John Henry's ghost at the tunnel, et cetera. Mr. Phillips gives this as a characteristic confusion of Henry and Hardy, but explains that they are often regarded as two different men.

Miss Elsie Scott [48] of that section, reports her father without mentioning Hardy: "Dad worked with John Henry four years at Big

---------------

48) Beards Fork, W. Va.

_____________________________________

35

Bend Tunnel. He was a Negro and left a son. Dad says he was the hero of the world. Dad knows a lot ahout old timers." The tunnel was built in two and a half years.

Sam Williams [49] was not at Big Bend, but says that he heard of John Henry while the tunnel was under contruction:

I was working at Hawk's Nest, that tunnel there on the C and O, when John Henry drove steel with the steam drill at Big Bend further down below there. People coming down the line told us about it. They said John Henry and Bill Dooland drove steel together. That's what they said. I never did see old John, but they said he was a big powerful man. I am 84. I turned steel for the steel-drivers. When I worked at Hawk's Nest, I worked for Major Randolph.

Mike Smith,[50] seventy-three years of age when he made his report in 1925, had a somewhat wider range of experiences on the road, and thinks there was such a man:

I worked in putting the C and O from White Sulphur Springs to the big cut below Kanawha Falls. I worked a while with the surveyors, but later drove steel in tunnels. I didn't see John Henry. I think there was such a man, and he drove steel. I heard about him when they were working on the Big Bend Tunnel, They talked about him driving steel there, and getting killed.

B. O. Jones, [51] a farmer of Albemarle County, Virginia, says that he worked the public roads in his neighborhood with "statute labor" during the seventies and eighties, and that at various times had in his gang Negroes who had worked on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad. Among them he mentions Tom Hill, Tom Carey, and Ned Johnson, and says that these Negroes were continually singing "John Henry. " He remembers that Tom Hill often talked of knowing Henry at Big Bend, where he claimed the steel-driver died from sickness about the time the tunnel was completed. Mr. Jones says that he worked no statute labor after 1889.

Mr. Logan, [52) a native of Wythe County, Virginia, says that he went to Big Bend Tunnel to work when he was "between 16 and 17 years old":

I drove steel for Blevins four months at the east end of Big Bend Tunnel before they got the shafts in. Blevins was a foreman there, and he went from Smyth County right by Wythe. I remember seeing Mike Breen and Jeff Davis. I didn't see John Henry. I didn't hear anything said about a great steel-driver. When I went back to Ivanhoe, people would come in there from the tunnel and talk about John Henry driving steel with a steam drill. They had a song on it, and it was a whole lot longer than the John Henry song they sing now.

--------------------------

49) Bluefield, W. Va.

50) Hinton, W. Va.

51) Ivy, Va.

52) J. M. Logan, Polvnell, W. Va.

____________________________________

36

I heard the song often before Big Bend Tunnel was finished. Mike Breen and Jeff Davis were very conspicu'otts among the-workme

at Big Bend Tunnel. A full acaount of its construdion should mentic:

them on the first page. They taught the Negr'oes there how to d:

four days' work in one daY.

Sil. M. Coleman, ee; whb was retired by the Chesapea-ke and Ohr:

Railroad in 1926 and put on the pension list, says that he was bc:

Dick Deans, and Aaron Bailey, and Anthony Jones worked on :

first crew, and off and on for a long time afterwards. They were : ;

strapping Negroes from Campbell County, Va. They were always sinl:*

*treri tnly worked, and 'John Henry' was their best song' they likec 'i:

the best.

They worked in Big Bend Tunnel, and all of them said theYtd s?':,:

John Henry drive 3g:-:--':-

in Bedford CountY, Virginia,

completed started to work a

River", and has worked at

Virginia and !(est Virginia:

John Henry drive. Dick Deans said he saw

the steam drill, but I don't recall anything he

said John Henry was the most powerful man

and soon after the 6'C and O \\'li

track force on a section of the Jar.*

different places afll along the line -:

said about his death. T::

theytd ever seen, rawboney and as black as he could be"

These Negroes are all three dead. Dick Deans was working for rrri

at the time when he got killed on the railroad track.

A large number of these repofts__connect the Henry traCllm

with the dhesapeake and Ohio, and all -but - two of them place ::llt

steel-driver in itre constructi,on of Big Bend Tunnel, built -bet'"-:*-:

1870 and 1,872. Some of these witnesses have been employed at ' :l*

time or another on the road, but all of them testify to he":;;

elsewhere ,of John Henry, not at the tunnel. The four foll: I -{

reports were made by men who have lo-ng- Service records vith' :::rs

railr,oad, two of them being employees of the company now anc -:r1:

on the pensi,on list, and who testify to hearing the tradition i;: ;3u'

immediate Big Bend communitY.

Cal Evanls,6r) who aooked for railroad p-eople around the n;":rlr

off and,ofl for forty or fifty years' and who had an-opporrr:'l:'

therefore, to learn itl early history, state-s that he heard the re::lmr

of Henry's connections there when he first moved into the ii:,i'I'

borhood, and has heard them ever since.

E. S. Scott 55) states that he works for the ('C and O pe: ! #;

and started with them in 1879". He says:

I helped to clear out a wreck in Big Bend Tunnel in 1881.

the people there at the work then sing John Henry that beat the steam drill drill down, and I've heard it ever since then on the road, but I don't sing it and never did.

--------------

53) Mt. Carbon, W. Va.

54) Talcott, W. Va. See p. 13 if.

55) Montgomery, W. Va.

_________________________________

37

I remember how they talked about John Henry being such a great steel driver, and I won't more'n about twenty years old then.

Big Bend was first arched with timber, and John Hedrick states, in the next chapter, that he had charge of that work. Falls in the

tunnel I caused several wrecks the first few years after its construction,

resulted in the timber being replaced by a brick arch, beginning

rte early eighties. Cal Evans, already menti,oned, cooked for the,

n on this job. Tom !ilood 56) says that he has lived at Big

fifty years, worked thirteen years helping to arch the tunnel

dfu brick, and is now on the pensiion list of th'e road. He adds,

n we were arching the tunnel along in the eighties, holes in the

dirg were pointed to as those John Henry drilled. People here

the neighborhood still talk about hearing John Henry driving steel

fre funnel. Any noise in the tunnel, Iike dropping water, is liable

now to scare some of them.t'

J. E. Huston is a telegraph operator for the Chesapeake and Ohio

, and is stationed at Big Bend where he has worked for

company since 1893. He was living there when the brick arch

begun, and remembers that the workmen often spoke of the holes

6e heading as being drilled by John Henry:

When I was a boy, we boys here in the neighborhood used to play

played, (This

iving. We used sticks for hammers and sang as we

hammer killed John Henry', and so on.

The John Henry story has been in our family

SQ Bend Tunnel in 1881. My father worked for

they moved him to Talcott in 1881. After we

talk with the people around the tunnel time

ever since we moved'

theCandORailroad,

moved here I heard

and again about the

t John Henry had with the steam drill.

-\ly mother had two old Negro house servants, a man and his wife,

wmlh quite often spoke of the steel-driver. They were certain that he was

ftffi in the big lill at the east end of the tunnel.

Obviously the old Negroes are the best chroniclers of the Henry

fiFdition. Like the svs:mpla of the faithful, their tales are first-hand

ud, have the force of reality. That of William Lawson 5?) is charac-

rurimd by marvels that hardly need excite distrust. 'He reports his

lrrryt as eighty-five and the place of his birth as 'Laudin County,

rlrilfratnia, where his mother, 106 years old, still lives. During the

,{lmctr War he was on both sides, first with the Confederacy and then

'mffi the Uni,on, but regards himself first of all as a farrner:

I was living on A. S. Masseyts place up Falling Spring Valley when

CI, rmt to Big Bend Tunnel in the spring. My brother Armstead was already

,kc- I went to him there and stayed ttil time to cut corn in the fall.

ffi ras the year they put the hole through.

Armstead was along with John Christian and John Turner in the

i {ing, and I drove steel under Armstead. He showed me where to drive.We were driving from the east end.

----------------

56) Talcott, W. Va.

57) Charleston, W. Va.

____________________________________

38

When we met a dispute arose between the two sides about who was the first man to drive a light hole through. My brother said he did, and they fussed about it all itt.t evening. Next morning when we- starte:

*oiking again they started the dispute again. My brother and ltrill Christias'

(Will ri"rJto* the other side) shot each other dead. Armstead said,'Yo,::

gun ain't no bigger than mine', and they both fired about the same tin:t

will Christian hii my brother right plumb in the heart, and my brother

hit him: a little on the side further toward the middle of his breast' Bc':'lr

of them were dead in five minutes after the guns cracked.

I was the first to get to Armstead, and turned him over. He ie'li

his face. Then C. R. Mason come. They buried him on the mountainsrst

a government graveYard.

When the hole was put through there was a

in the tunnel, and that's what started all the fuss'

put the crowbar through first, but it was the drill'

The hole had been put through three or four months when j mrn

Henry was killed. He ttt th. best steel-driver I ever saw' He was shu:nr'1i

and brown-skinned, 'and had a wife that was a bright colored woman 'nel

was 3'5 or 35, and weighed 150 pounds'

\J{/hen I went there they had a steam drill in the tunnel at the

end. They piped the steam in. They had a little coflee-pot engine on

outside. They didn't use it in the heading, but on the bench an:

the sides.

John Henry drove steel with the steam drill one day, and b5a! it

but got too hot and died. He fell out right at the mouth of the

They put a bucket of cold water on him.

His wife come to the tunnel that day, and they said she carnf;

body away, I dontt know. I never saw anybody buried at the :

except my brother. They said they shipped some of them awa\'" lutr

didn't see anybody shipped away. I don't know where they burit:

Christian. They didn't bury him with Armstead-

The time John Henry killed his self was his own fault, 'cause:

he bet the man with the steam drill he could beat him down. John Henr"'

no man beat him down, but the steam drill wontt no good ::

John Henry was always singing or mumbling something when bt

whipping steel. He would sing over and over the same thing som

Hetd sing

'My old hammer ringing in the mountains,

Nothing but my hammer falling down't

A colored boy tround there added on and made up the John Henr-'

after he got killed, and all the muckers sung it.

C. R. Mason was the boss rnan at the tunnel. He was a good'

old man, but he was a tough man. Hetd spit on you all the

was talking to you. His son was named Clay Mason.

The historical residuum of this first-hand report is certain-.-

very considerable. C. R. Mason built Lewis Tunngl rel not Big ;

The two are on the same road, fifty or sixty miles apart, and went

---------------

58) Tunnelling, p. 962ff.

______________________________________

39

under construction at the same time. There seems to be no government graveyard at Big Bend, and no reason for one. Lewis Tunnel is just across the line in Virginia, and Mason employed convicts of that

rfrte ix buitding it.se) In all pr,obability he required a graveyartd of

rme sort, and rnay have called it the government graveyard. From

rying until ti,me to cut oorn in the fall is the wrong time of the

guen for a 3(dirt" farmer to be away on a construction job. If he had

rurrrt the other half of the year at Big Bend, he might have had a

,fuce to take part in opening the tunnel from the east end to shaft

rG- It was opened in February, 1872.00; Minor inconsistencie,s, of

mrse, may be expected in a report of evertts a half-century 4go,

lh Mr. Lawson sets up a case in aonflict with major matters all

fug the line. Possibly he has confused his own experiences at Lewis

l[inunel with the Henry traditi,on of Big Bend. At all events, he is'

rmn rnanufacturing fnom the whole cloth, and his is accepted in this

as a popular report.

A report such as $/illiam Lawson's, or Newton Redwine's,

something of the energy of the Henry tradition, how difficult

uould be to take its full measure. Its echoes come from a very

area, but chiefly from the South, from Negroes and white people,

people of varied interests and connections. \il. C. Handy, the

blues artist, and O. W. Evans, a newspaper editor and

isher, add their authority. Most of the contributors, however,

laborers, active or retired after a lo,ng period of service: steel-

, pick and shovel men, cooks, and farmers. Scattered all along

line, they establish the tradition as early as the seventies. Several

it before 1880. Others testify to its wide diffusion in the eighties.

y' heard it in Alabama, and Evans in Virginia, both in the eighties.

The Henry traditi,on -could hardly have originated before the

uction of the steam drill into railroad construction in the South

I$70. It must betrong, then, to the seventies, the earliest date

by its diffusion. Its place of origin must accord.

Almost half of the reports, and practically all of the fuller onrs1

te a definite place of origin. The larger vote connects it witlr

ft extension of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad across West

lftginia between 1870 and 1873. Before following up this claim, I

examine briefly two others, the Alabama and Kentucky clairns.

The case for the Kentucky lifters need not be considered at all.

Redwine, hovever, has heard authoritatively, as he supposes,

King's Mountain Tunnel of that state is basic in the tradition,

he fails to consider adequately the fundamental drilling-contest.

construction of this tunnel was later than that of Big Bend, and

to follow up Mr. Redwine's report have added nothing of value.

The Alabama claims are more difficult. In addition to the steel-driver's Alabama and Tennessee connections already presented, Dr.

------------------

59) Lynchburg Daily Virginian, Lynchburg, Va., Jan. 1, 1872.

60)The Greenbrier Independent, Lewisburg, W. Va., Feb. 19, 1872

__________________________________________________________

40

Johnson published three reports of the tradition in that section [61]. One mentions "Shea & Dabner", and another "Shay and Dabney," as the contractors for whom Henry worked. All three mention the drilling-contest. One places it at "Cursey Mountain tunnel." Another says that he "was shipped to the Cruzee Mountain tunnel, Alabama," where the contest occurred. They vary in their dates of the event from 1881 to 1887. Dr. Johnson, unable to find the mountain tunnel in Alabama, or elsewhere, dropped the matter for want of "any sort of objective evidence."

Possibly "shipped" means more than a trip on some river of Mississippi or Alabama. The name "Cruz," is not unusual and

possibly Henry shipped to Santa Cruz Mountains of Jamaica.

Walter Jekyll collected in Jamaica, around 1900, a iong of ri-*r-

stanzas, a ('schottische or 4th Figure", a version of the Jotrn H.:,*'

so.ng adapted for dancing. Two of its stanzas a:re built on the l :*1

"A ten pound order him kill me pardnert' and ((Den number :dmr

tunnel I would not work d6". Mr. -Jekyll explained the song in ::*,

yay: '(An incident, or perhaps it were bettei to say an aciide.: il

the making of the road to Newcastle. A man who undertook n f, *,1r*r

of contract work tor 910 was killed by a falling stone. The so-;-i *s

tunnels are cuttings. Number nine had a very bid reputati,on.,, ii

whiJe there seerns to be some question about ihe characte:

the road to New Cas{Ie, tunnels and open cuts occur frequenl-,. rur

rai,lroads il Jamaica. In a length of less then thirty-eight mile! Lu:

one line, there are twenty-two. or) The first railroad cJnstructi,_: yr

Jamaica dates from 1843 to 1845, but was not pushed untiJ the e.:,,

eighties. 0+; The opportunity, therefore, exisied for the sons ri

develop its railroad connections in Jamaica before 1g20. t, .outo '-a,{r

mlSlatec! to the United States and become adapted in the constflrit,rnlll

of Fig Bend runnel. Trade between Jamaica and this countrr-

well established at the time and would have pr,ovided passage,

source might account for tunnel number nine in two tixts df ,.

Henry't_'s) ald for the popular belief in the steer-driver's coming

England or Spain, or from "columbust' or ((cainrr, as announce:

other texts of the ballad.66)

Furthermore, the theory for Jamaica as the source of the l. nrn

lgnfY song might have some support from the testirnony of tu,ii.,r

Gilpin, who will appear in the neii chapter. Among his ,iunrr. iil1,

the song- are two of "shoo Fly", and among the clai"ms, as publi.:*u

in- the Virginia newspapers of the time, foittre origin bt hir \r!*'

minstrel success was one from the rMilmington lournal ,r,:',im

maintained that '(its dulcet notes first broki upon the worlj ffi

---------------------------

61) John Henry, p. 19ff

62) Jamaican Song a Story, publications of Folk-Lore Society,

Folk-Lore Society, London. LV (lO{M).2bR

63) " T ra n s_po,rf - p.o'uie *; -l;- ^ ju *-t. u'; j " f rr

London, Nov. {0, tgZg.

64) Teh handbook of Jamaica 1882, p.

65) Appendix. p. 114. J o u r it at , XXVftI (19i5i,

66) Appendix, p. 110. John Henry, p. 121.

__________________________________________

41

Nassau, N. p., during the blockade, and was first imported into Wilmington by some of the blockade runners." [67] Versions of Jekyll's

and t'Shoo Fly", then, may have had currency in the West

s and migrated to the United States together, or separately,

Big Bend Tunnel was begun in 1870.

The theory that the Henry song first developed its railroadr

ections in this country, possibly at Big Bend, and was then

nlanted into Jamaica seems equally safe. Raih.oad construction

: during the eighties, or subsequently, would have furnished the

ion. Possibly the Cruzee Mountain Tunnel has a greater value

this theory.

d recent letter addressed to the Public Works Department of R. Fox, Chief

the other frorn

i-ca has resulted in two reports: one frorrn H.

reer of the Jamaica Oovernment Railway, and

i Farquharson, of the Public Works Departm,ent.

E-rcerpts from Mr. F,ox's report:

lhe No. 9 Tunnel (now known as No. 12 Tunnel) at the 32 Mls.,

*.r;s. from Kingston was built during the construction of the Extension

niles of track) from Bog lValk to Port Antonio which started in

lS94 and finished on July 1896. This tunnel is 464 feet long.

This construction was carried out by an American Syndicate headed

r .\tr. J. P. McDonald and was more locally known as the McDonald

\ Jamaican labourer named John Henry is said to have died from the

r:i of constantly striking drills with a 10 1b. hammer on the work at

i Tunnel, which was then notoriously regarded as a difficult task in

::nstruction. In Jamaica, particularly at those times, any incident of

,t|l1llim "qind was bound to attract great notice, and somebody thought of the

illrttuuii cf commemorating it with a song, the words and rhythm appealing

rilrl ::e imaginative spirit of the labourer" The song, 'Ten pound hammer

,ttttti;rl* ne pardnert soon took the hit, and was not alone popular amo'ng the

iiurirtnrrrrers on the Railway construction but was everywhere sung by labourers

rrtttri ,, rmaica.

The West India Improvement Company lrom the U. S. A. built the

riiirilliiii''n'av from Porus to Montego Bay 1B0l-94 and sublet to the McDonald

';nn:any who built Bog \)/alk to Port Antonio Line 1894-96.

.\1r. Farquharson's report begins enigmatically:

The bridge fo,reman on the road Frankfield John's Hall Corner Shop

Road Policy Works, worked on the extension of the Railway to

Antonio and' I saw him on the 7th Inst., and asked him if he knerv

i,mrn'::ing about the incident at the No. I tunnel. He gave me the follow,ing -nformation :

This song originated when the No. 9 tunnel was in course ol con-

ml::jon.

I:: fixing the centering for the lining of the tunnel, wedges were being

r'"',:r up by' a rman using a 10 lb hammer. The structure collapsed and

---------------

67) The Staunton Spectator and General Advertiser, Staunton, Va., Feb. 1, 1870.

____________________________________

42

killed some 11 people. The name of the man alluded to in the song as 'me pardner' was John Henry. The song therefore runs'-.

hammer him kill me pardner.'

No accident of the kind ever happened as far as I know on t;-t

Castle Road and none of the cuts were numbered, they never are' a:

I have never known this to be the case. At times appropriate nalr!:s

given to cuts, such as tsmellhellt, tSee me no more' etc.

Steam drills were used on the construction of the line, but not"rlory

known of any competition having taken place between steam dnls

hand drills.

Thc Iollowing names are known: -

Dabner, in charge of blasting operations.

John Henry, checking up cuts and embankments.

Shea, Engineer in charge.

Tommy Walters, Assistant Pay Master.

Santa Cruz Mountains, in contact with the road fro,m Pt-rrui

{A ten

Montego Bay, might explain Dr. Johnson's Cruzee or Cursey fulou:

Dabnei and- Shea, though not mentioned by Mr. Fox, would pcsi

be connecting links. nut I am not greatly interested in testing

evidence on -this point, and on several others, regardin-g somt

which the reports ieem to be in conflict. The essential drilling-c'c

is wanting. It is sufficient for the theory under way that tv-c

stru,ction companies from the United States were in Jamaica bex

1891 and 1896. The reports show that the John Henry song g

its currency there at the time, several years to'o late for the orig-r

the tradition. Atrong with these reports, the Public $ilorks Depan:m

of Jamaica, through the help of Martin Barrow, very k_indlv

municated a version of the song,6s) two lines of which, ((l comt

Merican to put this tunnel through" and ('Ooing buddy to my cou:

seem to complete the case.

Of the two theories for the Henry tradition in Jamaica, that

origin and that of its adoption, the evidence favors the second-

doJs not, however, fully explain the tradition in Alabama. The a:"

drilling-contest in particulai is still a heavy it._T. Possibly the rer

of Heiry's connections in that section are all of a popular lis

even though the personal touch enters into the account of a ce

chroniclerf and like Mr. Lawson's, in conflict with major n3:

show tOo trnuch. They will probably deserve more attention as auti

records when the place where the alleged aontest occurred is :

in Alabama. At all events, the construction of the Chesapeake

Ohio Railway in West Virginia has priority claims' and the obq

leaning of the tradition woudd seem to promise more in that state.

--------------

68) Appendix, p. 99.