Conclusion- Chappell 1932

Close-Up: Driving Steel; R. Matteson 2010

[This is Chappell's conclusion (briefly edited) which begins on page 80 and ends on page 92. Footnotes are at the end of each page. Despite Chappell's criticism of Dr. Guy Johnson's work, he also throws his hat in for the West Virginia origin; the setting- the Big Bend Tunnel.

R. Matteson 2014]

CONCLUSION

To explain the John Henry tradition, authority has brought forward all sorts of theories, several of which are no longer important. The theory that "John Henry" and "John Hardy" are one has been out of date from the first, and recourse to variations in current tunes of the two ballads for their original separation is not only unnecessary but highly questionable. Their texts dispose of the theory once and for all. They are mixed in comparatively few versions, and their stories, based on two groups of facts about a quarter of a century apart, are different. Their structural similarity, however, may not be

entirely accidental.

Among the things that appealed to Dr. Cox as significant in his confusion of Henry and Hardy, was the "passing of the song into the possession of white folk, and the rapid introduction of conventional elements of balladry." [1] His is the theory of elaborate mystification, if not something better. Dr. Combs would seem to have less use for such puzzles: "Ni John Hardy, ni John Henry (The Steel Driving Man) n'ont pris leur origine parmi les blancs ... Les deax chansons . .. sont sans conteste l'oeuvre de noirs. The Yew Pine Mountain [a version of the John Henry song] est un rejeton de John Henry." [2] As to this relationship between the ballad and the song, Dr. White is in agreement, [3] but Dr. Johnson prefers something better. Among other things of interest, he thinks that the "work song type of John Henry probably antedated the ballad type," and that the ballad type required more time in the making."[4] His emphasis on the detachment of '(John Henry" from work is in line with his treatment of its hero, and he probably thinks that both are products of the middle-class parlor. The first to report the ballad and the first to take a position as to its origin was Miss Bascom:

"Obviously not a ballad of the mountains, for no highlander was ever sufficiently hard-working to die with anything in his hand possibly a plug of borrowed 'terbac'." 5) Her objection to highlander has been echoed often with equal authority.

The theory that "John Henry" and "John Hardy" are entirely Negro products has obvious difficulties. Compilations such as T. W. Talley's Negro Folk Rhymes and N. I. White's American Negro Folk-Songs show that the Negro's product is mainly

-------------

1) Journal, XXXII,512.

2) Folk-Songs du Midi des Etats-Unis, p. 104.

3) American Negro Folk-Songs, p. 189.

4) John Henry, p.69.

5) Journal, XXII, p. 249.

___________________________________________

81

a different sort, the song type rather than the ballad type. American Negroes have had ample opportunity for ballad-making: they have had tragedies before and since those of Henry and Hardy. How often have they made a ballad on such occasions, immediately after the incident, or for that matter at a later date? The events giving rise, to "John Henry" and "John Hardy" took place in southern West Virginia where the mountain people rarely fail to produce a ballad when something of the kind occurs. Theories, then, for the origin of the two ballads must take these facts into account.

Fortunately "John Hardy', with its relation to the John Henry tradition accounted for, requires no theory in this study. "John Henry" and the Henry song, however, gain something from new light in the tradition and the construction of Big Bend Tunnel, the gangs at work on the tunnel and the larger tunnel community at the time. The tunnel community and the tunnel repertory are important. That gangs of laborers, especially gangs of Negroes, sing as they work with hammer and pick is a matter of common knowledge, and those at Big Bend were no exception. The testimony shows that they were encouraged to sing. [6] W. J. Yoder, a tunnel engineer, says: "Their chief characteristic was to strike in time. Their accompaniment of weird and monotonous chant (sometimes pitched in a minor key) to the sound of clinking steel made an impression upon a sensitive ear not soon to be forgotten."[7)

The Big Bend community was made up of white people and 'Negroes, with an occasional variant, and included not a few celebrities.: liquor-peddlers, fortune-tellers, liars big and bigger, banjo-pickers, ballad-singers, and at least one pagan beauty. They were all there, some drunk and some sober. The region ten or twenty miles around could easily add greater variety on occasions of jollification, and provide larger resources for the tunnel repertory.

The full character of this repertory cannot be known, but doubtlessly it included a large number of popular songs. Mention has already been made of "Shoo Fly," "Lynchburg Town," "Liza Jane," "Pawn My Watch", "Tell the"Captain, I'm Gone," and "Can't You Drive Her Home, My Boy ?" It was, of course, in a state of flux, and as time went on and materials accumulated tended more and more to develop a community character. Ballad-singers and banjo-pickers always have a batch of old songs, and make adaptations, often new or almost new creations, when anything meriting such interest occurs. Tunnel Negroes, as well, pay tuneful tribute to their work, to the events of the day, and of the night before. Mr. Hill says the Negroes of Lewis Tunnel 'usually sang a song they had composed

------------

6) Charlie Littlepage, of Charleston, W. Va., who says that he built the foundation for Yorktown Monument and helped to build the Chesapeake and Ohio across West Virginia, states that singing was encouraged among his Negroes and generally on the road and that he once discharged a foreman who tried to stop them.

7) Journal of the Western Society of Engineers, II (1897), 61.

______________________________________________________

82

on their work, or the foremen, or some 'loose' women around the camps."

Possibly these Negroes had composed such songs,' but they were quite certainly still composing, or decomposing, them at every singing. The available texts of "John Henry" evidence such composing. It exists in unmeasured variety. Mr. Wallace says that it "used to be that every new steel driving-'nigger' had a new verse to John Henry." Mr. Barnett, a white man, can sing it all day, when working, by improvising stanzas as he goes along. "Every 'nigger'," says Mr. Thompson who has heard, "hundreds of different verses" of the ballad, "seems to have his own words and verses, so it would be difficult to state that any one certain series of verses were the original song, if such ever existed."

Some of the contributors, however, seem to think that "John Henry," has had better days. "It was the leading railroad song," says Mr. Sanders, "but they've tore it all to pieces and sp'iled it." Mr. Evans remembers a few stanzas from forty years ago, and adds that there were quite a number. Mr. Logan reports that Negroes from Big Bend, before the tunnel was completed, had a song on the drilling-contest, and that it was longer than the versions sung now in his locality. The ballad, then, seems to have existed, from its early days, in what one observer calls "quite a vocabulary of verses."

Just how many stanzas "John Henry" contained at first is, to say the least, a delicate question. And I must confess a lack of faith in the doctrine of recurrence motifs as a means of determining the original of such a ballad. As a work song its gains and losses from adaptations to varied situations must have been too great for the argument of recurrence, unless of course it is confined to the basic episode of the drilling-contest, and I am not certain that that is altogether safe. It leaves too much out of account, as other matters that must be considered will show.

It is no longer necessary to look for a distinguished poet of New York or Georgia as the author. An example of his work has already come to light in the broadside Dr. Johnson published from Blankenship. [8] His treatment of John Henry as a railroad man, under the title, "John Henry, The Steel Driving-man", alone rules out the poet. That Big Bend workmen were miners is shown by the only published record known from the inside of the tunnel. [9] Negroes employed on the tunnels during the second half of the 19th century were usually in the service of private contractors and generally referred to as miners, especially by the press, and around tunnels in the South the select men who drove steel with hammers or sledges before the innovation of machinery into that sort of work were designated as steel-drivers and still are for the most part. The ballad has a tunnel background, and its hero is a steel-driver. His relation to the tunnel personnel, his captain, boss, foreman, turner, and shaker, shows that. Moreover

-------------

8) John Henry, p.89.

9) p. 64.

_________________________________

83

he is characterized as such in the ballad. In all probability the next printed text of "John Henry" that turns up, certainly if it is the work of a poet who thinks that a railroad man, a miner and a steel-driver are one, will be broadside number two.

Blankenship's closest rival known [10] is W. C. Handy, who presents the steel-driver at Muscle Shoals, Alabama, as driving more rivets than a compressed air drill"[11] a peculiar victory, as distinctive of course as that of driving more rivets than any other drill, and not unlike that of driving more rivets than a compressed air brake, or a jig saw. Proportionately, John Henry strikes fewer discords in the work of Roark Bradford, who presents him as an expert hog-catcher, only fair as a woman-catcher, and very ordinary as a woman-keeper. He presents him also as in expert cotton-picker, roustabout, railroad man, and might have added his prowess as an iron-breaker or watermelon-catcher. Mr. Handy and Mr. Bradford are interested in the Henry tradition as a highly diversified development, and neither has anything to say about tunneling.

"John Henry" is not the record of a railroad man, riveter, or hog-catcher and must have originated while the tradition was confined to the Big Bend community, before it became widely scattered and the steel-driver became somebody besides himself. Presumably credit for its authorship belongs to the gangs at work on the tunnel, or to ballad-singers and banjo-pickers of thee neighborhood. Other things being equal, about the same degree of probability rests with either side.

In at least one important respect, however, other things were hardly equal. The tunnel management discouraged anything that weaken the morale of the Negroes. If John Henry was killed about the tunnel, he could have been cerebrated there only us a hero, and then in no way that emphasized his tragedy. The ballad record of his death from the drilling-contest, an incident apart from common experience at the tunnel and therefore less likely to cause trouble, would have had no encouragement among the gangs while on duty, or while they were under the observation of tunnel officials. This

-----------------

10) Frank Shay and Alfred Frankenstein have some interest in this connection. In 1820 says Mr. Shay, in Here's Audacity, p. 249, "the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad began a spur through West Virginia. When the surveyors arrived Cruzee Mountain they found they would have to tunnel." Neither Cruzee Mountain [possibly Coosa Mountain, Alabama] nor the tunnel has yet been found in West Virginia or near the state, but his heroic sketch presumably allows one anywhere. As his authority for for John Henry he cites Dr. Johnson who is still trying to find Cruzee mountain in Alabama. While Mr. Frankenstein in his prize poem, "John Henry: An American Episode" The University Record (University of Chicago), XV (July 1929), 153 seems to show correct observations for bid cities, the Civil War, and Jim Langhorne's nieces he is out of step for every significant detail of the basic locality. It is not necessary to ask what these two writers would have printed a ballad of John Henry's drilling-contest at Big Bend Tunnel provided they were adept with the so called traditional ballad manner.

11) P. 31 ff.

____________________________

84

best explains the failure of Miller, Jenkins, Gilpin, and the Hedricks to remember anything about the ballad in the construction of the tunnel. Consequently, celebrities of the larger tunnel community have a better claim to its authorship.

"John Henry", nevertheless, belongs to the tunnel. An outsider could not have realized it. A casual acquaintance with the tunnel and the so-called traditional ballad manner would not have been sufficient. Although the Big Bend repertory shared "Liza Jane," and other tunes with the general popular repertory, its larger part was purely local a large volume of personal stuff, the miners' memoirs and diaries in one. Acquaintance with this volume, with at least a taste of Big Bend sweat and blood, was necessary for authorship of the ballad. Its author, therefore, if it had an individual author, must have been a community celebrity and a miner in the tunnel. He had ample opportunity for its composition outside the tunnel organization, with or without assistance from other miners and neighborhood celebrities.

The tunnel personnel included several writers of verse, of whom three are on record. [12] Of these only one, Mike Breen, could possibly claim authorship of "John Henry." He was a local celebrity and commonly reported as the most efficient foreman in building the tunnel. He was the sort of man who could do as much actual labor as any member of his crew and at the same time exercise full authority. He won most of the prizes given at the tunnel for progress in driving the heading. With the help of John Henry, he and Jeff Davis, another white man, are celebrated in the neighborhood as the builders of Big Bend Tunnel. Both had a hand in the rough and tumble of the place, at work and play. They were heroes of a frontier society, married women of their group, and spent the rest of their years in the community. Mike Breen was in the habit of writing verse, but nothing is known of his writing a popular ballad. Moreover, he was a foreman, and could not publish a report of Henry's death there. Hundreds of others shared his acquaintance at Big Bend, and no doubt several of them had equal or greater skill in ballad-making. Like him, the author must have worked in the tunnel, and had at at least one dance with the pagan beauty, and others of her sort there at the time. These women had important parts in the tunnel drama, and might well have had a part in the authorship of the ballad. They certainly had a part in the tunnel repertory. Some of them were ballad-singers and banjo-pickers, and some of them furnished themes for the miners' improvised singing as they worked in the tunnel.

--------------------------

12) J. P. Nelson, an engineer there for a short time wrote a fairly large number of short pieces during his long life, but claimed to know nothing about the authorship of "John Henry."

Mike Breen, foreman, wrote "Kate," a three-quatrain account of a battle at South Mills, N. C., during the Civil War printed in James H. Miller's History of Summers County (W. Va.) p. 476. Breen's family explains that he "was always writing poems."

The author of "Big Bend Times," was a laborer, but nothing further is known of him.

_____________________________________

85

The tunnel was very much alive, and these women had a finger on the pulse.

By way of preparation for a closer examination of the Big Bend repertory, an experience on the trail of John Henry has point. For seven or eight years one of my outposts has been the old shanty of a Negro shoeblack in Charleston, West Virginia. He is fifty or sixty years of age, rather good-natured, and at one time was a railroad man. When the right sort of a customer enters, he shines his shoes, brushes his coat, and makes his photograph while he waits. In the meantime he tries to find out something about the famous steel-driver.

On one of my visits to the shanty for a report, a big Negro, about forty years old and well dressed, entered, apparently for the purpose of spending an hour unmolested. The shoeblack, fully aware that this was no railroad Negro, said to me, with a twinkle in his eye, "This fellow can tell you all about old John Henry." And he did.

He told of Henry's boyhood, and ambition to become a great steel-driver. As he talked, he walked about the shanty, took off his coat and hat and mopped his brow with his silk handkerchief. He described the drilling-contest, explained how the turner turned the steel with a pair of tongs, and reached his climax in Henry's victory and death. There was a moment of waiting, a pause. Then he moved gradually, more dramatically, toward his second climax, the one defeat of John Henry as a steel-driver, his defeat by a woman, his wife. The role was about to end, and the actor was again waiting for applause, even more than he had waited after his first climax, but there was no response. He lacked the reality of his part, and his audience, the shoeblack and I, were disgusted. Silence, and tenseness, and the big Negro slouched into one of a half-dozen chairs, half-broken and half-mended against the walls of the shanty.

Eventually I remarked thus, as I must confess now with apologies: "Another damn lie! Who believes that a woman could drive more steel than the man who stood out as the hero of the hand-drillers in building seven miles of tunnels through hard stone ?" There was no answer and after a moment the shoeblack jumped up and scurried about the shanty. He picked up a rung from one of his broken grasped it with both hands, flung himself on the ground, held the rung upright between his legs, and threw his head back. He had not uttered a word. Then, looking the first actor straight in the eyes, he said with not a little bitterness: "This is the way to hold steel. A turner don't use no tongs. I turned steel." The play was over and the curtain was lowered, and Black Apollo soon sauntered out from the shanty and disappeared.

He not only lacked the necessary idiom, a touch of reality, but his credulity was astounding. Yet he is echoed by hundreds of Henry admirers, reporters of the tradition and singers of the ballad, and by not a few recent commentators. Their John Henry wears a one-piece suit, and never takes his boots off.

_______________________________________________

86

What is the significance of Mr. Hill's statement that Negroes at Lewis Tunnel usually sang of their work, foremen, or "loose" women around the camps? It is not that their songs were of two distinct types, good and bad, and that those about their women were more shady than the others. Like those of other tunnel gangs, Negro or mixed, [13] their local songs for the most part were all alike on that score, and even their popular tunes were adapted more often than not to the shady side of their affairs. When the foreman of a tunnel crew gets sick from bad liquor, or from anything else, the gang rewards his woman, not his grocer. In fact the grocer and other cornerstones of middle-class society are out of place in a tunnel. The management keeps the pot boiling, and the gangs work and felicitate each other on what happened last night and what is going to happen tonight. Notwithstanding what they may do as individuals outside their organization, as a group they delight in their fabliau, the more immediate, the better. Find fault with them if you like but the situation exists all the same, and provides their only escape from a continuous line of tragedy.

The advice of a farmer to his third son Jack, a piece of hearty humor among white people and Negroes of the South, is at least suggestive. The farmer, in whose home lives the teacher of the neighborhood school, divides a part of his wealth equally among his three sons, and promises the remainder to the one who makes the most of his first gift. The two older soon lose their birthright, and Jack, not being acquainted with Machiavelli, is about to lose his. Having pledged his heritage for a very great consideration, though somewhat limited, on the part of the lady teacher, he scruples about a larger performance at her urging and continues to answer: "Bargain's a bargain." The farmer, smoking his pipe and ('baking" his feet by the fire in the room below, and overhearing echoes of Jack's reaction to the lady's efforts to return the heritage, thinks his son doth protest too much, and yells: "Drive her home, Jack! You'll get everything." Tunnel gangs make this their own, and some woman whom know takes the place of the school mistress. They repeat each line, with the chorus "Driving hard, - - huh", two or three times, adding a grunt for each stroke of the hammer:

Oh, my baby, my honey gal - -

Hard to please, never done - -

Just one inch, was the bargain - -

Wants another, and another - -

----------------

13) Gangs on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in Virginia were mixed, and convicts from the penitentiary were used. "White and black are at work together; and I was told by one guard that he had more whites than Negroes under his charge. Their work is chiefly in Lewis Tunnel The State receives for their labor 25 cents per day, and the contractor clothes, feeds, and physics the convicts." New York Weekly Tribune, Nov. 8, 1871. Convicts were not employed on the line in West Virginia, but a great many white people, native Americans, Irishmen, and others, were used. Gangs on the road were mixed. White and black worked together.

_________________________________

87

I told her, 'Bargaints a bargain' - -

Done no good, not a bit - -"

Change her mind, right away _ -

Wants a yard, foot ain't enough _ -

wants my hammer, handle too _ -

Says, 'Be a man, like your old dad' - -

Drive her home, my honey boy, - -

Got my baby, millionaire. - -

Got a big farm, house on it - -

Got a fine horse, barn full of corn - -

Got a fine buggy, riding out - -

Got a steam mill, I don't grind there - -

Got a water mill, best in the world - -

Make a nigger, leave his 'lasses - _

Pharaoh's army, got drowned _ _

Falling in, the Red Sea - -

Forgot to lay, a rail across - -

Then the gang may. stop to replace the piece of steel with a longer or sharper one' or for some other good reason. Possibly the leader wants to scratch a tick. He changes the chorus to "Losing time, --huh", and starts the gang off again thus:

Told my baby, this morning - -

Just before, I left her - -

Take as much, as she wanted _ _

'Cause the ticks, eating it up - -

This thing goes on and on, with the number of motifs, and possible combinations, limited only by the memory and observation of the gang. Some motifs may not appear the second time. I have hard the tick stanzas sung only once, and then by a mixed gang with a white leader- He was a big man, more than six -feet tall, and weight to excess of two hundred pounds. Forced to defend his "baby," he time and time again took his Ingersoll watch in his ham-like hand and retorted: "It's the works, 'taint the looks." Although her face and arm were quite handsome, her neck imposing, she had the misfortune of being short and bow-legged. And the other members of the gang swore authoritatively that she was "bow-leg-ged" elsewhere besides in her "feet and legs."

These twenty-five stanzas, needless to say, are all shady, just as much so as those in which the gang calls a spade a spade, but their language is such that an outsider might miss the point. He would at least need to know the fabliau of the farmer's advice to Jack, the farmer who married a millionaire, and the lover who fell in and got drowned because he failed to lay enough rails across for safety. For a full understanding, he would need to know also the experiences of the gang, especially the women they are in immediate contact with. The outsider would not know all this. No one, moreover, not even one of the song-leaders, could possibly know the inside and out of a large tunnel organization, and at no time could he say what was

______________________________________

88

sung there the day before. He would have to account for dozens of gangs scattered over a distance of a mile or more and in all probability he could not account for his own. When such an organization, intact for two or three years, breaks up, the amount of improvised shady stuff that remains is very small. Probably nothing survives. Whatever finds its way into the popular repertory from such a source soon wears borrowed clothes, and may be ultimately become a sacred hymn.

If the reader happens to be a member of the Pulitzer prize committee that honored One of Ours as a realistic portrayal of life in the World War, he will certainly not expect a larger piece of tunnel realism. Yet he must not suppose that the subject is exhausted here. I have written thus to dispel the smothering clouds of romantic idealism thrown over the whole thing. An understanding of the tunnel repertory can be had in no other way.

I shall not insist that all the stanzas mentioned above were sung at Big Bend. "Big Bend Times" establishes a variation of the farmer's advice to Jack in the construction of the tunnel, [14] and that is as far as one can go. That thousands of such stanzas were sung there will not be questioned by those who are acquainted with tunnel gangs in the South. The ballad says that the "work is hard and the camp is rough"[15] and they will not object.

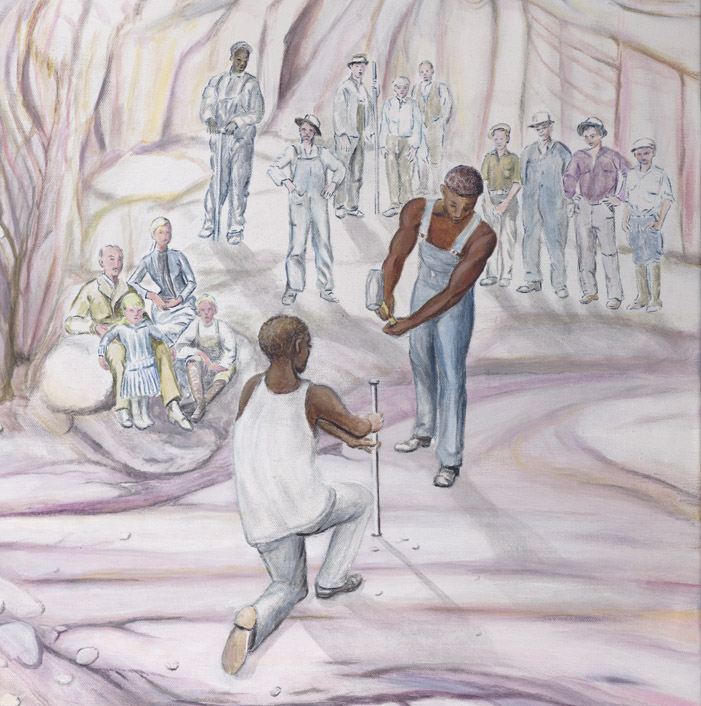

The preparation is such now, I hope, that the curtain can be drawn on the gangs at work in Big Bend Tunnel without offense to tender breeding. On the stage are hundreds of miners, mostly Negroes. and mostly naked. Here the miner wears a shirt, or a fragment of one, and the same may be said of his trousers and shoes, the other two parts of his wardrobe; but he has taken off his shirt, and I am not certain about his trousers in all cases. The heat is intense, the air filled with dust and smoke, and the lights from burning blackstrap are not at all adequate. Whatever the manner of turning steel in the heading may be, dozens of Negroes at least half-naked are sitting around on the bench holding with both hands a piece of steel upright between their legs, and the steel-drivers, two for each turner are singing and driving. Now and then the turner does the singing and the driller adds only a grunt as his hammer falls on the steel. The singing is largely improvised, capitalizing the inspiration of the women around the camps, and everything else in sight, especially that of a shady sort. That these half-naked Negroes could sit around holding a piece of steel upright between their legs for two years and

--------------------

14) In the testimony of George Hedrick, in this study, the line "Can't you drive her - - huh" is remembered from Henry's singing at Big Bend. This is much like the line "Can't you drive her home, my boy?" in Bend Times." published shortly after the tunnel was commented as sung by the Negroes at work there. Dr. Johnson, in John Henry, p. 39, reports Mr. Hedrick's line as "Can't she drive 'em!" This sounds well enough for the barnyard, to be addressed to a rustic maid who is about to lose control of her ducks or pigs, but has no place in the tunnel, and is not the line Mr. Hedrick reported to me.

15) John Henry p. 127.

____________________________________

89

a half without being celebrated in song is impossible of belief. Take a look, and then examine "John Henry." The following stanzas, or variations of them, are found in several texts of the ballad:

When John Henry was a little boy,

Sitting on his papa's knee,

Looking down at a piece of steel,

Says, 'A steel-driving man I will be.'

When John Henry was a little boy,

Sitting on his mama's knee,

Says, 'Big Bend Tunnel on the C and O Road

Is going to be the death of me.'

Is this not a reflection of the tunnel scene? Are the "piece of steel" and "Big Bend Tunnel" not companion symbols that explain John Henry's woman as an expert steel-driver? Will they not best explain why John Henry dies so many deaths on the mountainside, the woods on three sides of the tunnel camps with the river on the other where community dances were often held, and where doubtlessly he gave his red haired woman his hammer wrapped in gold, instead of sending it to her? This construction does not mean that the stanzas are always sung with full appreciation. It means only that the materials originated in this way.

The amount of sex symbolism in "John Henry" widely disseminated would be hard to determine. No doubt much of it was lost as soon as the ballad began its circulation in oral tradition. Common expressions, not understood as symbols, might easily be replaced, or jumbled sufficiently to mar their first meaning, with the result that the occurrence of motifs in texts written down fifty years later may not in all cases point in the right direction. this is equally true of other shady stuff in the ballad. The tendency to make John Henry a saint would naturally affect the argument of recurrence in determining its original form.

The explosion motif occurs frequently in the extant texts, but only once with this extremely vulgar connotation:

John Henry drove a spike up near the crown.

John Henry laughed when the boys all laughed,

said, 'It's nothing but my hammer failing down.[16]

In another case Henry's "hammah suckin' wind," [17] is the explanation, but more often than not it is the mountain falling in. Disintegrated rock was continually falling from the roof of the tunnel while it was under construction, but the explosion echoed in this stanza was

----------------

16) Ibid p. 119. This stanza may be added to the group I have already pointed out for Dr. Johnson, in the first chapter of this study. It is his and he insists that no vulgar version has ever fallen into his "net" (p. 141). I suggest that he try one the important sense faculties and if that is not sufficient he might employ the tuning fork he uses to separate phonograph and folk versions of the ballad.

17) Ibid., p. 97.

__________________________________

90

certainly much more frequent among the sweating gangs crowded together there. The stanza, then, is such that it would have little chance of survival in halidom, but might well have existed from the first.

The woman in the case seems even a better example of improvement. In not a few of the texts, she acts her part somewhat housewifely manner, with a heavy burden of faith and duty. She is not necessarily of the sort that follow construction camps, the sort characterized in this stanza:

John Henry had a pretty little wife,

He said, "Come sit on my knee.

You have been the death of a many poor man,

But you won't be the death of me.[18]

This is the sort of woman associated with the steel-driver at Big Bend, but she might have entered the ballad at some other camp. She could hardly have met John Henry for the first time in Dr. Johnson's "parlor". Possibly Henry's woman, the Big Bend woman, did not appear in the original form of the ballad. Her name is not there, not in the preserved texts, but this means nothing, unless of course it evidences the origin of the ballad in the community, where she was to well known. Being a white woman, she would have been masqued for her role, and eventually much of her energy and variety destroyed. She had only one dress, however, while the woman of the ballad changes her tone and dress often enough to have entered from all sorts of places. If Henry's woman is the woman of the ballad, she has improved her wardrobe, and that is quite possible, even probable. The same is true of the explosion stanza. Big Bend was full of explosions from falls of rock and from other sources, but no doubt the tunnel repertory included the old Negro explanation of rumbling in the ground as the result of Satan moving around. This motif, then, like the woman in the case, may be organic, a reflection of the tunnel, or it may be borrowed material, adapted as a part of the original form of the ballad, or subsequently. Much other stuff in "John Henry" is also found in popular song, and its bearing on the history of the ballad cannot be determined in any satisfactory way. Doubtlessly "John Henry" was sung to pieces as soon as it was sung together, and in a state of flux, as it exists now, gathered up scores of motifs in a day's singing.

As a work song "John Henry" is sung in various ways, sometimes over and over in this fashion, with or without a chorus. Getting one is the least of the steel-driver's troubles:

When John Henry, - - huh, was a little boy,- - huh,

When John Henry, - - huh, was a little boy,- - huh,

When John Henry, - - huh, was a little boy, - - huh,

When John Henry, - - huh, was a little boy, - - huh.

---------------------

18) Ibid., p. 128.

________________________________

91

With similar repetition other lines follow in order. When the leader finally built four stanzas on one from the ballad, he starts with a line from the second, the stanza that happens to occur to him, not always the logical or chronological one, resulting in a better order of lines in the stanza than of stanzas in the ballad as a social song. Such a performance on the part of the tunnel gang encourages the adoption of stanzas from other songs and the development of new material as the work goes on.

Possibly "John Henry" originated in this way. Certainly the little boy sitting on his papa's knee and "Looking down at a piece of steel" had its origin among the tunnel gangs at work. Other lines had a similar origin, and through the genius of the tunnel repertory a large body of material was ready for the ballad-maker, -whether or not he used any of it. He selected what he required to body forth the basis episode, the drilling-contest, just as he might have made a ballad from the four tick quatrains, by taking a line of each. Possibly there was no ballad-maker, and its form the product of tne gangs at work in the tunnel.

At any rate, the John Henry hammer song must have developed in connection with work of this sort, but speculation as to the time and place of its origin gets nowhere. Possibly it antedates the tunnel period in the south. Although it was sung by the men at work on Big Bend, its echo of Henry's death there might well have been later. Such would not have been allowed in the tunnel, and could hardly developed elsewhere in the community. As a social song there is comparatively little to recommend it, unless of course it is pushed in the direction of play games and dancing, and as such may have had earlier or later developments. Its connection with "John Henry" is very slight and seems only accidental, and can have no bearing on the question of the origin of the song. It is a topical song and has now preserved, deals chiefly with the hammer, but it has no basic episode and may exist without the hammer topic. "John Henry," on the other hand, is the record of the drilling-contest at "Big Bend Tunnel. The contest is the ballad, and the heart of the John Henry tradition.

Dr. Cox, the first important commentator on the Henry tradition in this country as already pointed out, has made his approach fro m the Hardy angle. He considers "John Hardy" "John Henry," and Henry hammer song all as one, with its modest beginning in the black belt and the "passing of the song into the possession of white folk, and the rapid introduction of conventional elements of balladry," an example of literary evolution in the 19th century, perhaps. Dr. Johnson comes later, with access to a larger bibliography on the subject, and yet with even a larger regard for the Negroid part in the evolutionary product. He is reminded of the "possibility that the John Henry hammer song could have sprung up almost immediately after the hero's demise, whereas the ballad type requires more time in the making." [19]. The hammer song is a thing of parts and any part,

------------------

19) Ibid., p. 69.

_________________________________

92

such as that echoing Henry's death, is the song, and the song could have come into being at any time. It is a work song, and as such in a state of flux occupies wide areas, without a basic episode, and with the possibility of a shift in emphasis from one motif to another around which all other parts, including borrowed or improvised parts from a day's singing, may be reassembled. Whatever the changes may be, the song remains. As a work song "John.Henry" is expanded in a similar way, and gathers up all sorts of stuff, but it has a basic episode, the drilling-contest, and as such it must be preserved, as such or ballad does not exist. Emphasis in another direction leads towards a new production, and possibly to "John Hardy"' Whether "John Henry" was composed by an individual or a group, its creation in all essentials must have required only a short time. I cannot agree that its basic episode, its unity, was realized in parts over a period of years, "required more time in the making." The drilling-contest was a matter of an hour or two, and in all probability the ballad was made soon afterwards, as several of the reports in this work indicate.

That the John Henry tradition is factually based seems too obvious now for serious doubt. The man in the case, notwithstanding what his real name was, or what became of him, was known at Big Bend Tunnel as John Henry, and is still remembered by a few who are certain of his existence, and of his activity there. Moreover, every circumstance bearing on the matter favors the reality of his contest with the machine and of his association with the freckled beauty. Although the amount of sex symbolism in the tradition cannot be determined in any satisfactory way, certainly the "piece of steel" among other motifs, and possibly even the drilling-contest not infrequently, all factual, have such values on occasion. Doubtlessly much of this material existed in the tunnel repertory at the time of the, contest between John Henry and the steam drill, and was utilized in the original form of the ballad. At all events, it is no longer necessary, or possible, to regard "John Henry" as made up of the whole cloth. The energy and variety of the Big Bend community will not allow it.