John Henry: A Folk-Lore Study- Louis Chappell 1932

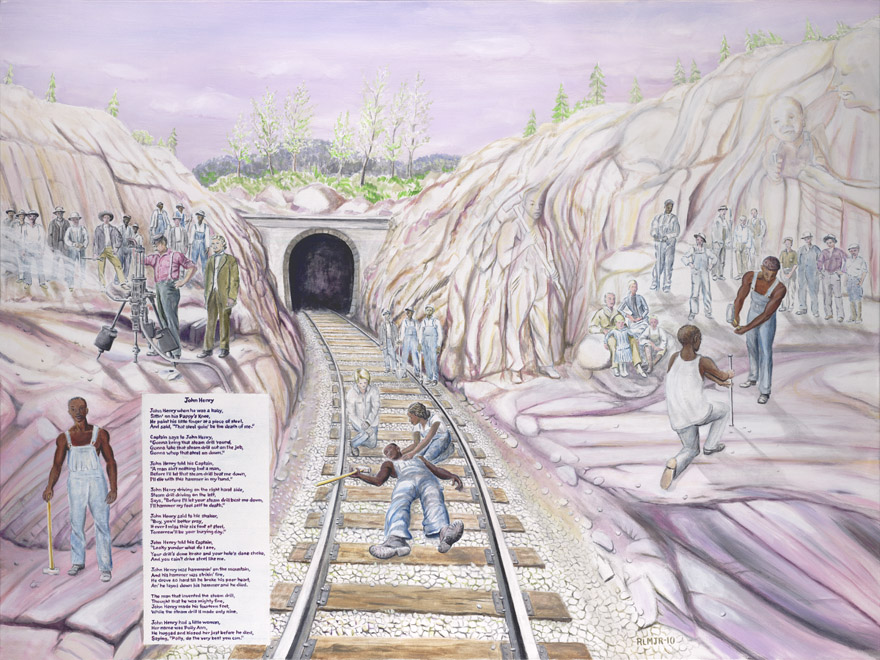

John Henry- by Richard Matteson C 2010

[Louis W. Chappell wrote John Henry: A Folk-Lore Study which was published in Jena, Germany: Frommannsche Verlag, W. Biederman in 1932. The 143 page book was included in compilation entitled, English Ballads, by Humbert; Willinsky; Chappell. The first part of this book is divided in three sections, the first two are in German and Chappell's is in English.

This page has the Title Page (with dedication), Contents and Preface- the other sections are attached to this page.

When Chappell (1890-1980) accepted a position at West Virginia University in 1921 teaching for the English Department, his association with John Harrington Cox ignited an interest in folk song collecting and research. His study of John Henry which Cox considered a variant of the ballad John Hardy showed that John Henry was an independent ballad. His book was reprinted by Kennikat Press in 1968. The strength of his book is the testimonies and attention to detail. The weakness are lack of dates for the ballad texts and no music. Chappell also repeats his points and some of the testimony over and over to the extreme.

In 1937 Chappell purchased a portable disk recording machine and recorded more than 2,000 songs and instrumental tunes which lead to his book, Folk songs of Roanoke and the Albemarle, published in 1939.

His collection is housed at the University of West Virginia. At that time, along with Chappell and Cox, were Josiah Combs who published his book, Folk Songs of the Southern United States in 1925 (Paris) and student collectors Carey Woofter and Patrick Gainer. Combs, who was raised in Kentucky in the early 1900s, started his folk-song and ballad collection there before moving to West Virginia. Both Woofter and Gainer have been involved with ballad recreation and false attributions (Linfors; Wilgus; Matteson) so I believe that their collected works should be viewed with suspicion.

A collected song by Woofter, The Yew Piney Mountains (a version of The John Henry song) appears in Chappell's introduction and was supplied to both Cox and Combs circa 1924. Woofter also contributed three version of John Hardy (see Appendix). It is not known if Gainer, who worked with Chappell, made contributions in the mid-1920s to Combs, Cox, and Chappell independently from Woofter (no contributions from Gainer are listed in Chappell' study), although folk songs attributed to Gainer's grandfather appear in the Combs collection. Gainer made a series of recordings for WVU of some of the Child Ballads in the 1960s and his collected songs began appearing in various publications until he published his 1975 book, Folk Songs from the West Virginia Hills, several years before his death.

The strength of Chappell's book is his attention to accurate details and his penchant for uncovering the truth. His extensive interviews were conducted only 40 or so years after the alleged incident of the contest with the steam drill -- a time when witnesses to the event were still alive and relevant testimony could be obtained.

The weakness of the book is the lack of dates and no music arrangement of the texts were made. Guy Johnson, who published his book, "John Henry: Tracking Down a Negro Legend" in 1929 and Chappell both seem to conclude that the Big Bend Tunnel in West Virginia is the location of the ballad. Both Johnson and Chappell mention the Alabama possibility but only briefly.

Today, more than 140 years later, the identity of the real man, John Henry is still being debated and the location of the contest is still left to doubt. When I started my painting of John Henry in 2010 (see different close-ups in every chapter) it was based on a site near Oak and Coosa Mountains, Alabama, and 1887 as the place and time of John Henry's race with a steam drill. This is the Alabama origin (as opposed to the West Virginia origin) as proposed by my friend, John Garst, who has studied the ballad in depth. Garst suggests the "Captain" of the song is Fred Dabney (born 1835), and that the Steel driver is John Henry Dabney, his slave, born c. 1850. Garst has written several articles and is still working on his book, detailing his research.

R. Matteson 2014]

_________________________________

JOHN HENRY

A FOLK-LORE STUDY

BY

LOUIS W. CHAPPELL

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY

JENA

FROMMANNSCHE VERLAG

WALTER BIEDERMANN

1933

Dedicated to: The Energy and Variety of the John Henry Tradition

___________________________

CONTENTS

Preface

I. Introduction

II. The John Henry Tradition

III. John Henry On the Chesapeake

IV. What Became of John Henry?

V. Conclusion

Appendix

Selected Bibliography

Index

___________________________

PREFACE

As a folklore figure, especially in the American black belt and border regions, John Henry is having a somewhat varied development but rightfully belongs to the rock-tunnel gangs, the hand-drillers of the frontier. He is the great steel-driver, and as a natural man flings himself, in a moment of triumph, against the machine of the industrial period after the Civil War. Like Paul Bunyan, he does impossible feats, but, unlike him, he often does them unassumingly. Thus he exists in oral tradition, and has not run, like Robin Hood, the full gamut of popular evolution, to the reductio ad absurdum of satiric parody, but with a greater metamorphosis has achieved diverse personalities and occupations, some of them superhuman, perhaps, but hardly as yet divine.

The amount and nature of the factual material that lies behind this widespread tradition has engaged the attention of several scholars, with a somewhat unconvincing variety of results. For the most part, they have added to its confusion in one way or another. John Henry was at first confused with John Hardy, another popular character in the folk-lore of the south; later he was set apart as purely mythical. These positions were taken without due regard for the tradition itself, and both have been revised or abandoned altogether. Presumably as a real man of flesh and blood, he has had some attention; but, more often than not, under the disguise of an objective treatment, a cloud of romantic idealism has obscured his more human qualities. Whether

as a man or a myth, scholars, strangely enough, have treated him the same and a new consideration of the whole matter, on the basis of a larger collection of data, seems necessary.

Although some ten years ago when this study began John Henry had been investigated at various points in the south, I was the first to discover the immediate region of his activity, as indicated by the tradition; and since then, with more than intermittent attention, I have followed his trail from the Great Lakes to the West Indies, and have repeatedly visited what seemed to be the most significant localities. Although some of the minor results of these investigations have appeared in the learned periodicals, the larger aspects of the subject seem to require the space of a monograph.

The contributors to this study are many, scattered far and wide. It is a pleasure to remember them, but they are too numerous to mention here. Thanks for helpful suggestions are also due to Dr. John W. Draper and Dr. Walter Wadepuhl my colleagues in West Virginia University.

Morgantown,

July, 1932

L. W. C.