Introduction- Chappell 1932

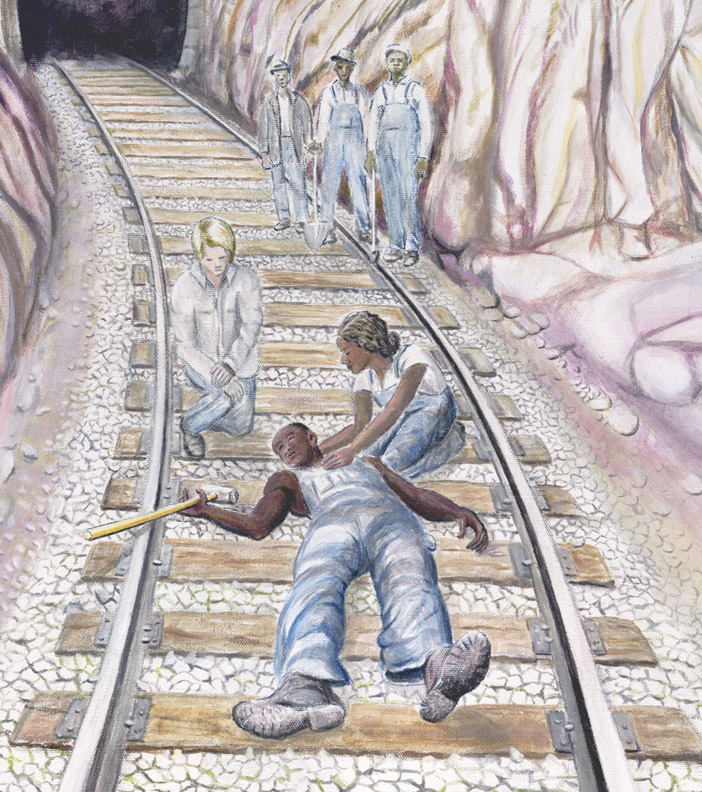

Close-Up "Death of John Henry" R. Matteson C 2010

[The Introduction is 20 pages long and as of now, briefly edited. The OCR scans were of poor quality and sections of raw text are not present here but still may be in other chapters. Footnotes appear at the end of each page.

The John Henry song is part of a large family of related songs titled "Take this Hammer," "Roll On buddy," "Nine-Pound Hammer," "Spike Driver's Blues," "I Got A Bulldog," and the song mentioned in Chappell's Introduction, "Yew Piney Mountains." These songs are not versions of the ballad and may or may not mention John Henry.

R. Matteson 2014]

INTRODUCTION

Interest in the John Henry tradition dates back to 1909, the year Louise Rand Bascom published, from western North Carolina, two lines of John Henry:[1]

Johnie Henry was a hard workin' man,

He died with his hammer in his hand. [2]

Along with this fragment, Miss Bascom contributed a version of "John Hardy"[3] the ballad of a Negro murderer and outlaw hanged in southern West Virginia near the turn of the century. In October 1910, two stanzas of John Hardy from Kentucky appeared in the Berea Quarterly, and the following year Shearin and Combs mentioned as current in that state both "John Henry" and John Hardy"[4]. In 1913, Perrow published versions of the John Henry song from Indiana, Tennessee, and Mississippi and a version from Kentucky [5]. The same year Professor Kittredge added a text of John hardy [6] communicated by Dr. John H. Cox, who had obtained it in West Virginia. The following year 'John Hardy" was again reported from North Carolina [7] and the John Henry song from South Carolina [8]. In 1915 "John Henry, or The Steam Drill" was reported from Kentucky [9], and another version published as "sung along the Chesapeake and Ohio Road in Kentucky and West Virginia" [10]. From 1909 to 1915 then, the John Henry tradition had ten reports and the John Hardy tradition had but five, with John Henry far more widely celebrated than his popular rival.

In 1916 W. A. McCorkle, ex-Governor of West Virginia, contributed a seven-stanza version of "John Hardy" with stanza 2 and 3 belonging to "John Henry", and gave out a popular report about John Hardy the steel-driver. . . famous in the beginning of the building of the C&O Railroad" across west Virginia about 1782, whop subsequently made his final exit in a killing down in the southwest

-----------------

1. Used in this study for the John Henry ballad as separate from the John Henry song. For examples of both types, see Appendix.

2. Journal XXII, 249

3. Ibid., XXII, 247. For examples see Appendix.

4. H. G. Shearin and Josiah H. Combs. A Syllabus of Kentucky Folk-Songs, p. 19.

5. E.C. Perrow Journal XXVI 163 ff.

6. G. L. Kittredge Journal XXVI 180-182.

7. F.C. Brown. Proceedings and Addresses of the 15th Annual Session of the Literary and Historical Association of North Carolina, p. 12.

8. H.C. Davis Journal XXVII, 249.

9. Berea Quarterly, Oct., 1915, p. 20.

10. John A. Lomax. Journal XXVIII, 14.

_________________________________________

2

part of the state. McCorkle characterized John Hardy as a "man of kind heart, very strong, pleasant in his address, yet a gambler, a roue, a drunkard, and a fierce fighter," a sort of composite character.[11] This account combines the tradition of the steel-driver John Henry and that of the outlaw and murderer John Hardy.

Following the lead of McCorkle's ballad text and hearsay report, Dr. Cox, in 1919, accepted John Henry as John Hardy whom he identified as the Negro murderer hang-at Welch, West Virginia in 1894, and treated the Henry ballad and song, as belonging to Hardy. Among the things that appealed to Dr. Cox as significant in this body of material were "the two groups of facts in Hardy's life centering respectively about the dates 1872 and 1894, which furnish the nuclei for three types of ballad as to content: (a) John Hardy, the steel-driver; (b) John Hardy, the steel-driver and the murdered; (c) John Hardy, the murderer"[12]. By 1925 he had succeeded bringing together nine versions of his "John Hardy" and in that year repeated his treatment of John Henry and John Hardy as the same man[13]. In 1927 he answered objections to his thesis with a call for further investigation of the subject,[14] and the following year renewed his request[15].

I have already considered that request in part by an examination of the Henry-Hardy problem from the Hardy angle, the approach Dr. Cox himself made [16]. I found that Dr. Cox had not taken fully into account the documentary records of John Hardy, that in his testimonial data he had given preference to hearsay reports, and that he had not shown proper regard for the wide diffusion of the John Henry tradition. My investigations, resulting in a fuller presentation, of background material largely corrective of Dr. Cox's publications on the subject, led to the conclusion that John Hardy is properly connected with the group of facts associated with the Negro murderer around 1894, the basis for "John Hardy," but brought to light nothing to justify treating him as the heroic steel-driver connected with the group of facts around 1872, the basis for "John Henry." With these limitations to the "composite" John Hardy, this study need consider the work of Dr. Cox, his methods as well as his conclusions, only in so far as it concerns the treatment of "John Henry," as a version of "John Hardy."

Among the nine versions of Dr. Cox's "John Hardy," [17] stanzas 2 and 3 of A, 1 of B, 1 of C, 1 of E, and all of H belong to "John Henry." The name John Hardy, however, appears in stanzas 10 of H and raises all sorts of questions; but, since the two are mixed in four of the other texts, and since the names

-----------------------

11) Journal, XXXII, 505 ff.

12) John H. Cox. Journal, XXXII, 505-520.

13) Folk-Songs of the South, p. 175ff.

14) American Speech, II, 227.

15) American Literature, I, 107.

16) Philological Quarterly, IX, 260ff.

17) Folk-Songs of the South, pp. 178-188.

_____________________________

3

and Hardy appear together in A, one is disposed to accept them together in H. This text, though, comes from Knott County, Kentucky, and the two ballads seem not to be greatly confused in that state. It appears moreover, that Dr. Combs contributed the ballad to Folk Songs of the South then published it himself the same year as "John Henry, The Steel-Driving Man," without the name John Hardy occurring in it. Such a significant difference on the part of the two noted ballad scholars in handling common material would seem to call for an examination of the texts they published relative to this study.

Their two printings of H have additional values in that direction. Dr. Cox uses the name "John Henry" for Dr. Combs "Johnny" in line 1 of stanza 2, "&" for Dr. Combs "and" in line 3 of stanza 2, and omits Dr. Combs' "that" in line 4 of stanza 9. Furthermore, the failure of Dr. Cox to continue his use of "etc." beyond stanza 6 resulted in the loss of "my babe" in line 4 and the necessary repetition for line 5 of each of the stanzas from 7 to 12 as given by Dr. Combs, whose mark for line 5 in stanza 2, and apparently for line 5 in all subsequent stanzas of the text, leads to a variation from his own pattern in stanza 1. Differences of punctuation and arrangement need not to be taken into account.

This version, it seems, passed through the hands only of these two editors, beginning with Dr. Combs as collector. An examination of "The Yew Piney Mountains," a version or the John Henry song contributed by Carey Woofter [19], and published separately by these two editors [20] has point in this connection.

Dr. Combs does not state when he obtained his copy of the song from Mr. Woofter, but he published it in 1925. Two years later Mr. Cox published it, without reference to its earlier appearance, and stated in a footnote that it was "communicated by Mr. Carey Woofter. . . October 17, 1924." Their printings show notable differences:

Refrain, line 4:

Combs: For that's my home, babe, for that's my home.

Cox: For that's my home, babe, that's my home.

Stanza 2, line 4:

Combs: But it'll not kill me, babe, it'll not kill me.

Cox: But it won't kill me, babe, it won't kill me.

Stanza 3; line 4:

Combs: But it'll not kill me, babe, but it'll not kill me.

Cox: But it won't kill me, babe, it won't kill me.

Stanza 5, line l:

Combs: Forty-four days makes forty-four dollars.

Cox: Forty-four days make four forty-four dollars

------------------

12 Josiah H. Combs. Folk-Songs du Midi des Etats-Unis, p. 191 ff.

13. Carey Woofter. Glenville State Normal, Glenville, W. Va.

14. Folk-Songs du Midi des Etats-Unis, 193ff. American Speech, II, 226-7

____________________________

4

Stanza 6, line 4:

Combs: O come back home, babe, O come back home

Cox: Oh, come back home, babe, come back home.

These differences are significant, and seem to belong to different versions of "The Yew Pine Mountains," but Mr. Woofter seems be an individual source.

What is the explanation of these discrepancies in common material in the hands of these two editors? Are those in the "John Henry" text to be accounted for on the ground that Dr. Combs furnished Dr. Cox a copy different from that he used in his work? Are those in "The Yew Pine Mountains" text to be accounted for on the ground that Mr. Woofter varied his copies of the same version of the song? Possibly the editors were using different versions of the ballad and song and their variations can be explained in that way. Their editorial notes throw no light on the matter, the answer must come from Dr. Combs and Mr. Woofter.

The fact that the former has not published his texts the second time and that the latter's ballad collection is still in manuscript form does not permit an examination of their practices in handling such material, but fortunately Dr. Cox can be tested on that score. His bibliography of 1925 [21] shows that of his nine "John Hardy" he published five, A to E inclusive, in 1919, and that before this date one of them, version E, had had two printings, one by Dr. Cox himself in 1915 and the other by Professor Kittredge in 1913. Four of these texts show important variations in their several printings and E develops a new stanza.[22]

-----------------

21. Folk-Songs of the South, p. 177.

22. Version A contains seven stanzas, and shows seven differences in its two published forms. The word "quarry" in line 1 of stanza 2 in the printing of 1925 is "quarrie" in that of 1919, "stays" in line 2 of stanza 5 of 1925 is "stayed" in that of 1919, "an" in line 4 of stanza 6 of 1925 is "and in that of 1919, and "a" in line 3 of stanza 7 of 1925 is "the" in that of 1919. Line 1 of stanza 7 of the printing of 1925 is "Friends and relatives standing around," and that of 1919 is "Friends and relatives all standing 'round." The second "was" in line 3 of stanza 2 and "damn" of line 5 of stanza 5 are not shown in the text of 1919.

Versions B, C, and D show fewer variations in their two printings. In B the word "mama" in the printing of 1925 is "mamma" in that of 1919. In the two printings of C no important differences appear. In D the pronoun "he" in line 1 of stanza 1 in the printing of 1919 is not in that of 1926, and "that" in line i of stanza 5 in the printing of 1925 is not that of 1919.

Version E was contributed by Walter Mick, Ireland, W. Va. Dr. E. C. Smith, Department of Government, New York, University collected the text several years ago and while he was a student in West Virginia, University communicated to Dr. Cox, who passed it on to Professor Kittredge for publication in the Journal. It's two earlier printings that of Professor Kittredge in 1913 ind that of Dr. Cox in 1915, are much alike, and the two later, that of 1919 and that of 1925, both by Dr. Cox, are much alike, differing materially in only two words. The word "answer" in line 3 of stanza 4 in the printing of 1919 is "answered" in that of 1925, and "Oh" in line 1 of stanza 7 of 1919 is "O" in that of 1925, with "answer" and "O" found in the earlier printings is contracted into "I'm" in those of the later

__________________________________

5

What is the explanation of these discrepancies in the work of a single editor? Does their character indicate a return to the practices of 18th century ballad scholars, a modified form of development by accretion? Or can they be explained on other ground? I am not disposed to find that Dr. Cox has had his hand-in matters beyond his province. Yet probably some of them are typographical errors, and others may have resulted from confusions in handling a large number of manuscripts, possibly during years when he was overtaxed from other work. His confusion, in this connection, of "C. E. Smith" for E. C. Smith, "E. C. Sparrow," for E. C. Perrow, and "Negro Work-A-Day songs [27] for Negro Workaday Songs possibly shows too great reliance on memory. Such variations, however, in his two or more printings of these texts seem to render unnecessary the inquiry Dr. Guy B. Johnson states that he made of Dr. Cox concerning the appearance of the name John Henry in stanza 3 of version A. [28]

It follows, then, that the appearance of the name John Hardy in stanzas 4 and 10 of H may evidence an extension of there methods in editing the text; but one will be inclined, although reluctantly, to depart from mere happenstance, as an explanation in this case because his variation from Dr. Combs' "John Henry, The Steel-Driving Man," provides a basis for classifying the version as belonging to "John Hardy," a turn in line with his treatment of the two ballads as one, and the two men as John Hardy whether Dr. Cox, however, is actually responsible for the name John Hardy in the text must be determined finally by the copy Dr. Combs, the collector, furnished him. John Hardy has a way of getting mixed up with John Henry,[27] and possibly the methods of Dr. Cox as shown in his texts from A to E did not affect his H. Nevertheless, this version, with or without the name of the outlaw, belongs to "John Henry." [30]

--------------

two, "did not" in line 2 of stanza 5 of the earlier two is contracted into "didn't" in the later two,. and "yaller girl" in line 3 of stanza 5 in the earlier two is "yaller gal" in the latter two. The most significant difference, however, between the two earlier and the two later printings is the addition of a 5-line stanza, stanza 6, of the printing of 1925 and 1919 but not found in those of 1915 and 1913.

23. West Virginia school Journal and Educator XLIV (1915), 216. Cf. Journal, XXVI, 180. XXXII, 516, Folk Songs of the South, p. 182

24. Journal, XXXII, 513. Cf. Journal, XXVI 163. Folk Songs of the South, p.177.

25. American Speech, II, 227.

26. John Henry. p.66(n).

27. Newman I. White. American Negro Folk-Songs p. 189. Dr. White says: "Miss Scarborough (126, p. 218) accepts Cox's opinion without discussion, but the songs she quotes mention John hardy only." They mention John Henry only, and his bibliography gives the date of her book as 1925.

28 Fortunately no general destruction of "John Henry" texts has resulted from these discrepancies. The most notable case that has come to my attention appeared in the Fayette Tribune, Fayetteville, W-Va., April 22, 1925.

_________________________________

6

In 1925, the year Dorothy Scarborough accepted without discussion Dr. Cox's treatment of the Henry and Hardy traditions as one, Dr. Combs objected, and explained for "John Henry" and " John Hardy": "Elles ne sont pas davantage deux variantes de la meme chanson... Le recit dans John Henry est entierement different." [29] Two years later Dr. Gordon called attention to the distinction between the two ballad heroes, and added that their songs are often "somewhat confused by the singer". He characterized Hardy as a "desperado; Henry a good-natured, almost lovable steel-drivin' man." [30] The following year Dr. White agreed to the separation of the Henry and Hardy traditions. [31] These investigators of popular balladry in the South added little, or nothing to what was already known about "John Henry," and, made no great effort to. They did little more than object to such use of Henry material as that Dr. Cox had made in taking it over for his composite John Hardy.

Dr. Odum and his colleague, Dr. Johnson, published in 1926 eleven texts of "John Henry" and four of the Henry song, inclined to believe that John Henry was of separate origin and has become mixed with the John Hardy story in West Virginia." They went even farther in suggesting probabilities. Having failed in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia to turn up any biographical material for Henry as a real person, they concluded he was "most probably a mythical character." [32]

Their fabulous John Henry apparently did not satisfy Dr. Johnson very long. The following year, after seeing the report of my investigations at Big Bend Tunnel on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in West Virginia, [33] he renewed his inquiries, culminating in a change of heart about where to look for the hero and a shift in point of view. "All in all," he writes, on the strength of this new information: "John Henry and Big Bend Tunnel are so intimately connected that there, if anywhere ... we must look for the origin of the John Henry tradition [34] and prefers "to believe that (1) a Negro steel driver named John Henry at Big Bend Tunnel that (2) he competed with a steam drill in a contest of the practibility of the device, and that (3) he probably died soon after the contest [35].

--------------------

29. Folk-Songs du Midi des Etats-Unis, p. 104.

30. R. W. Gordon. New York Times, June 5, 1927.

31. American Negro Folk-Songs, p. 189ff.

32. Howard W. Odum and Guy B. Johnson. Negro Workaday Songs, p. 221 ff.

33. In September, 1925, I investigated John Henry at Big Bend Tunnel and in February, 1927, a 10-page report of my work there fell into the hands of Dr. Johnson" I had written the report to preserve my priority claims until I could complete a larger plan of investigation on the subject, and was trying to get it published at the University of North Carolina. The following is Dr. Johnson's only acknowledgement: "I wonder to what extent collectors have made John Henry famous at Big Bend! I know of at least two others who were trailing John Henry there before I made of my visit." John Henry, p. 34(n). It would be interesting the other culprit.

34) John Henry, p. 26.

35) Ibid., p. 54.

____________________________

7

In taking this new point of view, however, Dr. Johnson, in 1929, says he began in February, 1926, to persue this new idea that the Big Bend tunnel was the place of origin of the John Henry tradition [36]. What he "means by the expression "to pursue the idea is not altogether clear, but his treatment of John Henry as a myth from. investigations elsewhere as already shown, and his" statement at the time, several months after February, 1926, are clear enough:

Prof. J.H. Cox traces John Henry to a real person, John Hardy, a man who had a reputation in West Virginia as a steel diiver and who was hanged for murder in 1894. We are inclined to believe that John Henry was of separate origin and has become mixed with the John Hardy story in West Virginia [37].

If he began several months before publishing this statement "to pursue the idea" that the John Henry tradition originated at Big Bend Tunnel, why did he offer no objection to Dr. Cox's treatment of John Hardy as the famous steel-driver there? He knew that Dr. cox in taking over the Henry tradition, for Hardy was taken over Big Bend Tunnel, and that he had treated Hardy as the famous steel-driver in building it. The answer of Dr. Johnson is that was inclined to believe that John Henry was of separate origin and has become mixed with the John hardy story in West Virginia." In this connection, moreover, he fails to take West Virginia into account in his schedule for another investigator.

We have found a few Negroes who were not clear in their minds about Booker T. Washington, but we have found none in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia who had not heard something some time about John Henry. In other places, however, in Mississippi and Maryland, for instance, we understand he is not so well known. To trace the story of the ballad to its origin is a difficult task and one awaiting the folk-lorist [38]

He leaves Big Bend to Hardy and the question of origin of the Henry tradition to the folk-lorist, several months after 1926, and these concessions characterize his efforts "to pursue the idea" that the tradition originated in West Virginia until he saw my report from the tunnel.

His marvellous freedom in handling this material would seem to call for an explanation of some sort. But his disregard of my rights is largely personal and need not require the attention of readers who are not interested in trifles, such as an investigator's priority, where I seem to follow him without reference in this study. The book he published, though, raises some questions that must be of general interest.

His "low-down" on John Henry doubtlessly should have first place, but a full appraisal of his part in the book cannot be made,

-----------------

36) Ibid., p.31.

37) Negro Workaday Songs, p. 222(n).

38) Ibid., p.222.

______________________________

8

here. He says that there "are undoubtedly some vulgar versions John Henry in circulation, but none has ever fallen into my net. I can truthfully say that the following stanzas contain the only 'low down' I have ever heard on John Henry." [39] The following are his first two:

John Henry had a little woman,

Name was Ida Red.

John Henry had a little woman,

She sleeps in my own bed.

Old John Henry was a railroad man,

Washed 'his face in the frying pan,

Combed his head with the wagon wheel,

Died with the toothache in his heel.

He probably regards these stanzas as late adaptations, not basically a part of the Henry tradition, and as well his third example which is much longer. He might have added at least three others of value from his own texts:

John Henry told his woman,

'I've always did as I please.'

She said, 'If you go with that other bitch,

I will not let you see no ease.'[40]

John Henry had a little woman,

Just as pretty as she could be;

They's just one objection I's got to her,

She want every man she see. [41]

'Where did you get your pretty little dress?

The hat you wear so fine?'

'Got my dress from a railroad man,

Hat from a man in the mine.' [42]

Possibly the miner and the railroad man were both local merchants of a very neighborly sort, and one, if not both, of them a Santa Claus but the hat and dress would seem to indicate at least that she was not entirely disappointed. He adds, in this connection, his confession of faith in sex symbolism in "John Henry":

Realizing that John Henry contains excellent symbolism from the Freudian point of view, I have kept a watch for such versions, but I have never heard one. However, Prof. English Bagby, of the Department of Psychology of the University of North Carolina, tells me that he has talked to at least one Negro who definitely interpreted John Henry in terms of sexual symbolism 43].

---------------

39. John Henry, p. 140 ff.

40 Ibid., p. 127

41. Ibid., p.124.

42 Ibid., p. 126.

43 Ibid., p. 140.

_________________________________

9

Perhaps he watched too closely to be able to evaluate objectively all fell into his net. One of his texts contains these lines:

John Henry had a little wife

Who were steel corn fed [44].

Possibly "steel corn" means only hard corn, and he has "never heard one". The contributor, of course, is the only authority for the text, but he, like the editor, can answer only for himself,'not for the other thousand singers of the same version. If the "drill," "a piece of steel," "driving steel," and "bucking steel," have Freudian possible connections, as his psychologist would seem to recognize, he allows none of them such a bearing in his work.

While Dr. Johnson insists on speaking "truthfully", one may ask, in view of his handling thus such materials, how fully he realized John Henry contains excellent symbolism from the Freudian of view". His answer, though it hardly seems necessary, is vigorously expressed in his review of Roark Bradford's John Henry, a more recent treatment of the Henry tradition:

And now Roark Bradford has written a book about John Henry - - - but not the John Henry of the legend. His is a jazz version, so to speak . . .The old John Henry was a tragic, almost a sacred, figure. He symbolized man versus the machine. This new John Henry is a tragic personality also, but in so far as he symbolizes anything it is man versus woman 45).

Dr. Johnson had explained earlier that the word jazz deserves to head the list in Negro song for the "act of cohabitation" [48]. One thing at a time and that done welil must be the rule for his John Henry, the good man hero who did nothin' but work. A "parlor" hero of of the good old days when a leg was a limb and cold hands meant a warm heart. Parson Weems denied his Washington and Marion less. That it was not necessarily for John Henry, widely celebrated for half a century by the "lower" tenth of back alleys and construction camps, to borrow his sex frorn the upper crust requires no proof.

In handling dialect, Dr. Johnson seems equally authoritative. A sufficient illustration of his success in the field is his treatment of a "big wheel turnin' " as a "corruption of Big Bend Tunnel," with the explanation that a "common dialect pronunciation of 'tunnel' is 'tunnel' [47]." While a "big wheel turnin' " might mark a stanza or version of the ballad as corrupt, I prefer to regard it as a substitution for "Big Bend Tunnel", without the necessity of finding a dialectal value in "tunnel" for "tunnel." Nevertheless, he is able to characterize the dialect of Roark Bradford's John Henry as a "sort that never was on land or sea".[48] And he is probably right at that.

-------------

44) Ibid., p. 119.

45) The Nation, Oct. 7, 1931.

46) The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, April, 1927.

47) John Henry, p. 86(n).

48) The Nation, Oct.7, 1931.

__________________________________

10

In the field of popular literature, as well the innocence of Dr. Johnson is too evident from statement's such as the following: "When John Hardy came on the scene, only a few snatches of Henry remained in circulation in West Virginia." [49] He gives no data to show that he had made a thorough investigation of "John Henry" in that state for the last decade of the 19th century or the occasion "John Hardy" came on the scene. Moreover, on the basis of material in his hands at the time he might have said, without serious objection, that "John Henry" had travelled far enough to escape complete confusion with "John Henry" when the latter ballad began its circulation in oral tradition, and that would have been sufficient for the point he apparently wanted to make, an "explanation of the mixed versions of John Hardy which Cox has found."

His statement that the "author of John Hardy. . . must have been familiar with the structure of John Henry for he cast his product in exactly the same mold"[50] is made without giving any evidence that "John Hardy" had the author. The observed fact of their structural similarity hardly settles the matter of individual or multiple authorship for one or both of the ballads. If "John Henry"

developed by stages "required more time in the making"[51] as he supposes, why does he find it necessary to assume the author for "John Hardy"? Does he contribute anything by such an addition without reference, to the earlier statement "Les deux chansons trouvent etre d'une structure analogue"?[52]. This statement allows the possibility that the two ballads derive their structural pattern from a common source, that "John Hardy" had its origin in West Virginia although when it "came on the scene, only a few snatches of John Henry remained in general circulation" in tbat state, or that the author of "John Henry" was familiar with the structure of "John Hardy" for he cast his product in exactly the same mold.

The separation of the two ballads is, perhaps, the best thing Dr. Johnson does in his discussion, and that is not altogether satisfactory. His materials and methods are hardly sufficient for his conclusions.

With two tunes of "John Hardy" from white people and several of "John Henry" from Negroes, he proceeds thus: "Jo hn Hardy

is simple, deliberate, and puts one in mind of the conventional English ballad sung by the whiie mountain people. John Henry is faster syncopated, and is much more typically Negroid than John Hardy [53]. Doubtlessly the tunes and rhythms of his examples

are somewhat different, but they are drawn too largely from phonograph records, college student, and other soloists, with improvements by the editor as the following pages will show, to have much value, and

-----------

49. John Henry, p. 64

50. Ibid p.64.

51. Ibid., p, 69ff.

52. Folk-Songs du Midi des Etats-Unis, p. 104.

53. John Henry, p. 66-67.

___________________________

11

such treatment of the two ballads does not take properly into account the frequency of Negroes singing "John Hardy,' and white people Jon Henry," both with notable racial variations and often a mixture of the two ballads in their performances.

He publishes a tune of "John Henry" from Robert Mason, who pick his twelve-string box "in more ways than a farmer can whip a mule," [54]; and another from Leon R. Harris, a rambler who worked in railroad grading camps from the Great Lakes to Florida and from the Atlantic to the Missouri River," who has wherever he worked "always found someone who could and would sing of John Henry," and who says, "The song is sung to many an air or tune, and hardly any two singers sing it alike.[56]" such reports are significant, and show more than the possibility of weakness of conclusions based on a few unrepresentative tunes.

Dr. Johnson, moreover, agrees that "the very essence of the work song is its fluidity, its adaptability to various kinds and speeds of "work' and that a "work song tune cannot be recorded with absolute accuracy [56] In his earlier discussion, he notes the inconsistency of the singer:

"When the recorder thinks that he has finally succeeded in getting a phrase down correctly and asks the singer to repeat it... he often finds that the reponse is quite different from any previous rendition. Requests for future repetition may bring out still other variations or a return to the previous version. Again, after the notation has been made from the first stanza of a song, the collector may be chagrined to find that none of the other stanzas is sung to exactly the same tune [57]. He adds in the next paragraph even greater difficulties for the collector recording "group singing in its native haunts": He cannot hope to catch by ear alone all of the parts - -and there are undoubtedly six or eight of many of these songs - - that go into the making of those rare harmonies which only a group of Negro workers can produce. . . He must be contented with securing the leading part of the song and harmonizing it later as best he can.

These explanations seem to place accurate tunes of the two ballads beyond the reach of Dr. Johnson.

Whatever he may think about the original authorship of "John Henry" and "John Hardy", he will hardly deny that they have -been hrough the seasoning process of group-singing, often with an exchange of units from one to the other and confusions with other similar rhythmic technique, with shifts in the "six or eight," parts for different occasions, resulting in first one part and then another holding the lead. A member of such a group, or any other, take only one of these parts at a time, as in the case of this collector, and must harmonize "it later as best he can," with

-----------

56. Ibid., p. 125.

57. Ibid., p. 90 ff. Cf. p.

58. Ibid, p. 69 ff.

59. Negro Workaday Songs, p. 242 ff.

__________________________________

12

the possibility of echoing the group or various groups in the several stanzas of the song. That all such soloists, or later groups, take the same leading part for their renditions is extremely doubtful. That the original "John Henry" and "John Hardy" could come through this process without modification is equally doubtful. It follows, therefore, that if one succeeds in bringing together enough examples to show tune end rhythmic differences in their survivals they will not be sufficient for the original character of the two ballads and cannot establish their separation.

Furthermore, their original separation on the basis of current tune variations ignores too much ballad tradition. If the author of "John Hardy," as Dr. Johnson insists, was familiar with the structure of "John Henry" and cast his product in exactly the same mold, in all probability he copied his "John Henry" tune also, or, rather that of his pattern. Possibly the author was one of a large group of ballad-singers who recognize only one tune for their entire repertory. Possibly the author, or some singer, transmitted the ballad as a "ballet" without tune notation, and all extant versions derive from this source. These are possibilities.

Weaknesses along such lines in the material on which Dr. Johnson bases his separation of "John Henry" from "John Hardy" place his thesis in an unfavorable light, and no great improvement of his case can be made from an examination of his tunes themselves.

they do not represent the full character of the two ballads requires no further explanation. His methods, though, of obtaining them have an importance, and they are well illustrated in his example from Odell Walker, his Chapel Hill authority for "John Henry".

He presents two examples of Mr. Walker's singing the first stanza of a single version of "John Henry",[58]; with tone and rhythmic variations, and fails to say which of the perforrnances is the correct one. Possibly he asked for the second singing of the stanza and failed to observe that his soloist had changed drinks. Possibly he had only one rendition, and as editor harmoni,zed r(it later as best he can." Nevertheless, he gives both exa:mpiles as Negroid, and uses them to show a difference between the two ballads. In fact, he must have succeeded in getting at least three performances by Mr. Walker, as lines 3 and 4 of the three printings of the first stanza of his version show: [59]

'Fore he'd let the steam drill beat him down,

Die wid his hammer in his han'.

An' befo' he'd let the steam-drill beat him down,

Die with the hammer iin his han'.

And before he'd tret the steam drill beat hfm down

He'd die with his hammer in his hand.

----------

58) Ibid. p. 248

59. Negro Workaday Songs

_____________________________

13

Possibly these specimens, with their several tunes, are faster, more, syncopated and "much more typically Negroid" than his "John Hardy" examples from white people. Apparently he published Mr. Walker's version in two other places, with further notable examples [60]. Such practices must of necessity affect the evidence drawn from his texts for any purpose. My request in a recent note on John Henry,61) for corrections by Dr. Johnson of a series of misrepresentations in the testimonial data he published from the Big Bend Tunnel neihgborhood has had no answer, and by way of throwing some light on his methods of handling such material a few of them may be pointed out more fully. One can easily understand that the slightest variation, conscious or otherwise, in these field reports would have significant results undder his system of classifying them as "positive, negative, or different" testimony. [62]

That Cal Evans he presents as follows:

'When the tunnel was under construction he was a youngster, not quite old enough to take part in the work. He thinks there might have been a steel-driver there named John Henry, but he never saw him and could remember nothing about him except what he heard later. He stated that while the story might be true he was inclined to believe that it was not [63].

Dr. Johnson would have no great difficulty in classifying this report for John Henry at Big Bend Tunnel as "negative, or indifferent," but if it is to have any bearing on the connection of the steel-driver with Big Bend and on the larger question of his reality, something more definite might be- expected from Mr. Evans. One would like to know why he failed to see John Henry , what he later heard and when and where he heard it. after investigating the Henry tradition there, one would certainly ask what story Evans doubts the truth of. Does he doubt the truth of the story of John Henry driving steel in the tunnel, the story of the drilling contest there, the story of his death as a result of the.contest, or the story of his body being thrown into the big fill at the east end of the tunnel? Or does he doubt the story that Henry's ghost is till driving steel in the tunnel?

Like many of the older Negroes of the community, Cal Evans, according to his own statement and that of his wife, followed the

Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad into that part of the state. He was a native of Albemarle County, Virginia, worked first on the road,

near white Sulphur Springs, West irginia later near Huntington, in the western part of the state and around 1875 began cooking at the roadhouse in Hinton, eight miles from Big Bend. In 1876 he married a woman of Orange county, Virginia. They made their home

---------------

60. The Southern Workman, LVI, 159, Ebony and Topaz, p. 48. Cf. John Henry p. 153.

61. American Speech, VI (Dec. 1930) 144H.

62. John Henry, p. 34

63. Ibid., p. 37.

__________________________

14

in Hinton, where Mr. Evans continued cooking at the roadhouse until arching the tunnel with brick was begun in the early eighties [64] Then he moved to Big Bend to cook for the workmen, and remained there. He had no opportunity, therefore, to see John Henry drive steel in building the tunnel between 1870 and 1872.

His contact with the tunnel for half a century made it possible for him to learn the stories of John Henry there, and hand his practice of telling them is a matter of general knowledge in the community. Although he objects to the reports of Henry's ghost driving steel in the tunnel, and of Henry's death as a result of the drilling-contest what he really believes can be understood only through an acquaintance with the man. He is one of the Negroes at Big Bend generally known to be afraid of John Henry at night- - not that he admits it of course, - - but this fact must not be overlooked in reporting his distrust of the ghost story, and of any other part of the tradition, such as Henry's spectacular death from the contest, which seems to him to contribute directly to it. He says that he saw, when the railroad was being double-tracked in the eighties, a human skeleton unearthed in the road bed over the big fill at the east end of the tunnel, where the dead from building the tunnel were reported to be buried at night; [65] but he objects to the skeleton as that of John Henry. He accepts, however, as factual the reports of Henry working in the tunnel and his contest with the steam drill.

Verification of this explanation of Mr. Evans can be made at Big Bend with no great difficulty. W. M. White,[66] a student at West Virginia University, who since he was a small boy has had a camp on Evans' place, about a hundred yards below the east portal of the tunnel, where he employs Evans to cook for him several weeks every summer, and where he has listened for hours in the evenings to Evans' tales of John Henry, says that Mr. Evans will not go alone at night to the tunnel, and that in going at night to Talcott, a small village just above Big Bend, he paddles his boat up Greenbrier River in order to avoid contact with Henry's ghost. Mr. Evans is much less courageous than Mr. Anderson the negro keeper or care-taker of the tunnel, who has what people in the neighborhood call a "pension job". On my first trip to Big Bend in the fall of 1925, I saw Mr. Anderson pushing a wheelbarrow filled with rubbish out of the west end of the tunnel, and called to him from the embankment fifty feet above and asked if he had seen John Henry while he was on the inside. He answered, with a Negro laugh, that he had no faith in the stories of John Henry and advised seeing John Hedrick, the man he regarded as knowing the facts in the Henry tradition.

-----------

64) I. H. Miller says that Big Bend Tunnel caved in during March, 1883, with the result that the railroad company was forced to arch the tunnel with brick. History of Summers- County, Virginia, 1908.

65. See pp. 37, 47.

66) Raleigh, W. Va.

______________________

15

Mr. Anderson explained how, in spite of the local fear of Henry's ghost he had taken charge when he came there more than thirty years before. He had had his most exciting experience on walking through the tunnel soon after his arrival. About half the distance through he had heard John Henry driving steel, and had experienced some difficulty in waiting for a closer acquaintance with the steel-driver he had been able to discover that what he heard was water dropping above the roof of the tunnel.[67]

It soon became clear, however, that his stories of John Henry were confined to the death of the steel-driver as a result of the drilling contest and the subsequent escapades of his ghost around the tunnel. Mr. Anderson believes that a man by the name of John Henry worked in the tunnel, and seems to think everybody else should. Like Mr. Evans, though, he was not at the tunnel while it was under construction and knows only what he has heard about the steel-driver.

As respects the Henry tradition, Evans and Anderson are both "positive" and "negative," but perhaps would cause the classifier no great trouble. They accept certain parts of the tradition as factual, and regard certain other parts as "stories." The investigator, therefore, who has a use for their beliefs about Henry must be on his guard to avoid misrepresenting them, as seems to be the case in Dr. Johnson's report of Evans' testimony.

Th same explanation can hardly be made in the case of John Hedrick [68] Dr. Johnson says that Mr. Hedrick "did not work on tunnel [69]" The reaction of Mr. Hedrick to this statement is about what one might expect from a confederate soldier after telling him that he was not in the civil War. Mr. Hedrick insists that he began with the first gangs at Big Bend and stayed on the job until the tunnel was finished. He quotes Mr. Hedrick as saying, "I did not see the contest myself, but I heard the men talking about it right after it took place." He fails to say where Mr. Hedrick was at the time of the contest, or where he heard the men talking about it. And it is important to know the meaning of right after it took place". Following this expression in the testimony, Mr. Hedrick speaks in terms of years not in terms of days or hours. Mr. Hedrick, however, claims that while the drilling-contest was taking place inside the tunnel he was "taking up timber" to be used for arching, and heard Henry "singing and driving" in the contest. Dr. Johnson is also misleading in his further statement, "Mr. Hedrick could not say whether John died after the contest, although his impression was that he did not." Mr. Hedrick is quite definite on the point, and does say with emphasis that Henry did not die immediately after the drilling-contest. This point on which Mr. Anderson, mentioned above, refers to Mr. Hedrick as authority in disposing of the factual basis for Henry's ghost in the tunnel. If Dr. Johnson had actually interviewed Mr. Hedrick, as he seems to expect the reader to believe,

-----------------

67. See p. 37.

68. John Henry p.40

_____________________________

16

possibly he would have made a different report. Mr. Hedrick and his daughter's family with whom he lives in Hinton, West Virginia, claim that the interview was not held.

Dr. Johnson, of course, will have his own explanation for these discrepancies in the testimony he published from Big Bend. But he will hardly find it necessary to explain why, after quoting Neal Miller as using the word "contest" for Henry's drilling-contest, he states on the following page that Mr. Miller "never spoke of the episode as a contest, but as a test", [69] or to explain the variations in his two printings of Mr. Miller's report, the third and last of the series I shall examine in this study.

The first printing of this piece of testimony is easily accessible [70] The second is as follows:

'This man, known as Neal Miller, told me in plain words how he had come to the tunnel with his father at 17, how he carried water and drills for the steel drivers, how he saw John Henry every day, and, finally, all about the contest between John Henry and the steam drill.

'When the agent for the steam drill company brought the drill here,' said Mr. Miller, 'John Henry wanted to drive against it. He took a lot of pride in his work and he hated to see a machine take the work of men like him. 'Well, they decided to hold a test to get an idea of how practical the steam drill was. The test went on all day and part of the next day. 'John Henry won. He wouldn't rest enough, and he overdid. He took sick and died soon after that.'

Mr. Miller described the steam drill in detail. I made a sketch of it and later when I looked up pictures of the early steam drills, I found his description correct. I asked people about Mr. Miller's reputation and they all said, 'If Neal Miller said anything happened, it happened'[71]. The first three quoted sentences of the second printing have no near parallels in that of the first. The fourth quoted sentence of the second is a statement of fact, and differs materially from the quoted statement of this fact in the first printing:

1st: "The test lasted over a part of two days."

2nd: "The test went on all day and part of the next day."

These are important differences in the facts stated and in the form of statement. The fifth and sixth quoted sentences of the second printing are statements of fact, and statements of these facts are quoted in the first printing; but the two printings show no similarity of form. The seventh and last sentence quoted from Mr. Miller in the second printing is also a statement of fact, but differs from the corresponding quotation of the first printing:

1st: "As well as I remember. .. he took sick and died from fever soon after that."

2nd: "He took sick and died soon after that."

----------

69) John, Henry p.42.

70) Ibid.. p. 40 ff.

71) Welch Daily News, (Feb. 22, 1930), Welch, W. Va.

_________________________________________

17

The qualified statement of Henry's death "from fever" in the first becomes an unqualified statement in the second, and the cause of death is omitted.

These are notable discrepancies in two printings of the same report by the same editor. Does he mean to offer the first or the second printing as the correct testimony of Mr. Miller? Perhaps he has a third version not less correct than the other two. Until he designates the authentic one, however, nothing can be done by way of testing its keeping with the facts as Mr. Miller claims to know them.

The materials Dr. Johnson uses seem less important in his hands than his shifting point of view. In 1929 he prefers to believe in the reality of John Henry, but is "not irrevocably wedded to this position". [72] In 1930, without additions to his bibliography of 1929, he is convinced of Henry's reality, [73] and for his stronger position relies heavily on Mr. Miller's testimony, the only one of the series in question reproduced in this connection. In its second printing he prepares for his sweeping conclusion by the addition of new information such as John Henry "took a lot of pride in his work", "hated to see a machine take the work of men like him," and "wanted to drive against it", and by a general toning up of the report by omitting expressions such as "as well as I remember." Moreover, he changes the quoted statement, "If Neal Miller says it happened, then it must have happened" [74] to a stronger one, "If Neal Miller said anything happened, it happened".

If Dr. Johnson toned up data for a stronger position when he became convinced in 1930 that Henry was real, in all probability he toned down the same data when he was "not irrevocably wedded to this position" in 1929, possibly because he was not fully divorced from his earlier spouse, his mythical John Henry of 1926.[75] His misrepresentations of Evans and Hedrick weaken their testimony for Henry's reality: those only slightly affecting their evidence affect it negatively, and some of them are more than slight. He almost succeeds in taking Mr. Hedrick out of the picture, and yet the value of Mr. Hedrick's correct report is about equal to that of Mr. Miller, the man he sets off as his important witness, his "One man against the mountain of negative evidence!" [76] a mountain of his own creation through manipulations under his system of classifying field reports as "positive, negative, or indifferent". After aiding all along the line towards such a consummation, he admits that one can make the evidence "lean either way"[77]. What was his purpose in such a method?

If one assumes that Dr. Johnson, in 1929, is masquerading in John Henry , capitalizing the wide distrust of testimonial data

-------------

72. John Henry p. 54

73. Welch Daily News, W. Va., Feb. 22, 1930.

74. John Henry, p. 53.

75 Negro Workaday Songs, p.227.

76 John Henry, p.53.

77. Ibid., p. 51.

____________________________________

18

and deliberately damning the steel-driver's reality with faint praise; he might find not a little influence of the mythical character 0f 1926. He would know, of course, that Dr. Johnson, before making his trip in June, 1927, had examined the report of another investigation at the tunnel, a challenge to his myth, and ,might find that he meant to play his trump card by publishing a report in conflict. An attempt to follow him, through an imposing line of manipulations, would lead ultimately to his testimony from Neal Miller, his "One man against a mountain of negative evidence!" Possibly he understood at least the theoretical value of a single affirmative witness on a point of disputed fact. Why, then, while joining the Talcott chorus in praises of Mr. Miller's reliability, did he destroy his testimony? Did he believe that one man could affect his relationship to his mythical spouse? When he became convinced of Henry's reality in 1930 without additions to his bibliography of 1929, did he abandon her altogether? Should one regard such implications as less obvious?

The hypothesis, at any rate, that Dr. Johnson deliberately set out to destroy the evidence for John Henry as real would possibly have to take into account his changes in "John Henry" texts and they can have no positive bearing on the matter, other than of course in so far as they evidence his wider practices in establishing a thesis. And, unfortunately, his earlier "objective studies" show the same cultural practices as regards first-hand materials. On one page in the first part of the book in which he created his mythical John Henry he offers the following lines brought more nearly up to date:

Goin' 'way to leave you, ain't comin' back no mo',

You treated me so dirty, ain't comin' back no mo'.

Where was you las' Sattaday night, -

When I lay sick in bed? [78]

He adds as source "songs gathered two decades ago" and published in another volume:

For I goin' 'way to leave you, ain't comin' back no mo'

You treated me so dirty, ain't comin' back no mo'.

Where were you last Saturday night,

When I lay sick in my bed? ' [79]

These improved specimens, faster, syncopated, and "much more typically Negroid", suggest what one might find in his work if he had continued to be equally specific as to his sources. It would be interesting to know just what his collection was before publication.

More recently, however, he says, in a review of Roark Bradford's John Henry: "one rather hates to see one's favorite American ballad and legend sprout more new variants between the covers of

---------------

78) Negro Workaday Songs, p. 20.

79) The Negro and His Songs, pp. 184, 185.

____________________________________

19

one novel than it would. in fifty years of normal folk growth. [80] What conclusion, then, does Dr. Johnson expect from a review of his own work? At least the name John Henry in version A of Dr. Cox's "John Hardy" should not have caused him the trouble of an inquiry. [81]

The methods of Dr. Johnson seem clear enough, and one need not urge an ulterior purpose on his part. That set forth in his preface to John Henry will take care of his work, "I conceive my mission to be to bring together and co-ordinate as much actual folk material as possible," That his apparatus, as set up for such a purpose is, not sufficient for handling historical evidence is to obvious, and one need not ask how much, of his collection he regards as "actual folk material." One need not emphasize his failure to distinguish between folk materials and direct or first-hand testimonial data. His desire, perhaps, to avoid dullness should be taken into account. He states in his preface that he is "not one of those who believe that folklore studies must be dull in order to be scientific." Yet he can hardly maintain that his methods are scientific.

He renewed his investigations in 1921, with the question: "Is this John Henry tradition true? I do not consider this question of any great importance."[82] In 1929 he concluded this question of whether the John Henry legend rests on a factual basis is after all not of much significance.[83] This position*is about what one might expect after examining his methods, and ample characterizations of his efforts in dealing with evidence for the existence of John Henry. Why he steps aside to exploit such evidence when he knows it is already in the hands of another investigator, is less certain. Whatever his full purpose may be, his manipulations have not destroyed the evidence of John Henry connection with Big Bend Tunnel, and the larger matter of Henry's reality.

At all events, in discussing -the John Henry tradition Dr. Johnson is identified with two points of view, the mythical of Georgia and the Carolinas and the factual of Big Bend Tunnel in West Virginia. The former he shares with Dr. Odum, and while ostensibly in the act of abandoning it welcomes Carl Sandburg to their camp[84]. The latter and the material for it, he seems "to regard as his won property and with marvellous liberality by way of invitations, to other researchers, and analyzes for their guidance, has handled it with great humility, and to the satisfaction of everybody[85]. When all is said and done, however, I must insist that he "doth but mistake the truth totally."

-------------

80. The Nation, Oct. 7, 1931.

81. John Henry. 66(n). He quotes the preceding page three stanzas of Dr. Cox's A, with five improvements.

82. Ebony and Topaz (ed. C. S. Johnson), p. 50.

83. John Henry, p. 54.

84. Ibid., p.6ff.

85. G. H. Gerould. The Ballad of Tradition. Cf. Louise Pound, Journal, XLIII, 126ff. L. C. Wimberly Folk-Say, A Regional Miscellany, -1930, p. 413ff.

_____________________

20

My purpose is to throw more light on the John Henry tradition. It has already had sufficient attention as a sacred thing. I shall take into account its greater variety and wider diffusion, and present a larger body of material showing its connections with Big Bend Tunnel. Dr. Johnson has taken care of its purely negative aspects in that locality, and I can confine myself mainly to the other side without undue regard for people who never saw or heard of the steel-driver. He will appear in this work as a human being, superior of course, but not without the common frailties of mankind.